The climate and ecological crisis cannot be solved without system change.

Greta Thunberg, UN Climate Action Summit, 2020

‘System change, not climate change’ is not a request we make to the current institutions.

Ecosocialist Encounter, 2022

Book inspired by knowledge co-production

A few years ago I began to plan a book on climate change, specifically on conflicts around false solutions versus grassroots alternatives. Although authored by me alone, it draws on knowledge co-production processes over the past decade or more.

My idea began from a political lacuna, namely: Despite greater demands for climate action and elite promises to reduce carbon emissions, fossil fuel usage was set to rise indefinitely (and now even more so since the Russia-Ukraine-NATO war). What has driven or facilitated the rise? What has been the role of false solutions for climate change?

Many insights have come from critical books on energy decarbonisation – actual, hypothetical or promised, often dependent on techno-optimistic solutions. This focus misses Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions from wider production systems, where putative fixes likewise depend on promissory scenarios. False solutions often have provoked protest linking many issues and societal groups, especially those most harmed by environmental problems (see Table 1). Such multi-stakeholder alliances would be necessary to drive a socially just decarbonisation agenda. Given the many political campaigns against such fixes, what can be learned from their strategies and outcomes? For academic research, political campaigns, and their linkages?

Credits: Biofuelwatch; Anthony Turner, CEO Visuals.

These questions led me to engage more with Climate Justice (CJ) perspectives on ‘system change’. Over the past decade I have participated in CJ activists’ discussions, involving knowledge co-production between activists and academics, some personifying both roles. These discussions analysed prevalent NGO strategies, their limitations, the elite’s false promises, and means to undermine them, especially by contesting the systemic causes of climate change.

As I further reflected, my long-time research on wider techno-fix controversies likewise involved civil society groups in knowledge co-production, sometimes more formally as Participatory Action Research. Our joint discussions diagnosed systemic causes of environmental problems, putative fixes evading those causes, and political strategies for contesting them. Such fixes were meant to be stimulated by market-type policy instruments.

They made promises about technoscientific advances, avoiding or overcoming negative effects of previous technologies. Sooner or later, advocates claimed that similar fixes would offer climate solutions. Examples include: ‘climate-smart agriculture’, claiming to sequester carbon through GM crops; 2nd-generation (or advanced) biofuels, claiming to reduce GHG emissions by replacing for oil; Advanced Thermal Treatments of municipal solid waste, claiming to reduce GHG emissions from landfill and through bio-based fuel products; and Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS), claiming to decarbonise fossil fuels (see Table near the end).

Those climate-mitigation claims provoked further controversy and critical analysis. Over two decades, my research benefited from such interchanges. So my book plan likewise has drawn inspiration from the collective insights gained.

To link all those aspects, I saw the need for a big picture. This could inform more effective campaign strategies against false solutions, while counterposing means towards system change. Such a framework could attract a diverse readership — researchers, NGO staff, wider activists, civil servants, etc. I obtained advice from many such people on my preliminary plan. That process shaped my book’s title, Beyond Climate Fixes: From Public Controversy to System Change.

This article conveys how my framework links CJ perspectives with academic ones from the STS and social movements literature.

Climate Justice versus techno-market framework

The prominent slogan ‘System Change Not Climate Change’ has sharpened public debate about the societal changes that are necessary to avoid climate disaster in ways creating an environmentally sustainable, socially just future. The demand for ‘system change’ directs attention at profit-driven high-carbon production systems which cause climate change, other environmental harms, resource plunder and social injustices, along with policies which perpetuate them. The slogan originated in the Climate Justice movement, especially in the run-up to the 2009 Copenhagen COP. It became more prominent in the 2019 School Strike for Climate and then the Fridays For Future protests. This agenda has overlapped with some Just Transition agendas (likewise Green New Deal agendas) for a socially just, low-carbon future.

Nevertheless, GHG emissions have continued to rise, alongside overall energy usage and renewable energy, which thereby complements system continuity rather than system change. This trend has been facilitated by techno-optimistic promises for low-carbon solutions. These have envisaged smooth pathways to decarbonisation, have encouraged a passive public to accept or await such fixes and thus have depoliticised or pre-empted societal choices about potential futures.

Indeed, some proponents have idealised future technologies as ‘climate fixes’ which would avoid the need for major societal change and so be more feasibly implemented. To reach the target of near-zero carbon emissions, ‘I am told by scientists that 50% of the reductions we have to make by 2050 are going to come from technologies we don’t yet have’, said the US government’s climate envoy John Kerry. His wishful expectation revealed the elite’s long-term alibi, namely: awaiting hypothetical fixes, and perhaps funding them, meanwhile continuing high-carbon production and consumption systems.

A key instrument has been market-type incentives. More than simply an instrument, this policy framework promotes a specific social order of market competition, often undermining cooperation. The concept ‘techno-market’ fix, already in the STS literature, seemed apt for naming the dominant policy framework of global policy elites.

A techno-market framework seeks to create new markets whose competitive forces will stimulate eco-efficient technological solutions. This policy framework arose from merging two antecedents, ecological modernisation and neoliberal environmentalism. Political responsibility for outcomes can be conveniently displaced from states to anonymous market forces and/or to technological barriers: no one can be held accountable for failure.

For a long time, a techno-market policy framework has been elaborated through carbon credits and trading, especially under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol of the UN Climate Convention. The European Union likewise has a long history of techno-market frameworks. EU policy more generally has anticipated and promoted technoscientific development as central to societal progress, thus depoliticising policy choices and responsibility for them. The promised environmental remedies have served to perpetuate GHG emissions. Both institutions remain complicit in climate change, despite their pretensions to global environmental leadership.

Nevertheless recurrent public dissent has often re-opened technical and market issues as political ones, pressed state bodies to defend their versions of the public good and counterposed rival futures. This analysis provides a rationale to identify a non-state social agency, at least in the global North.

Social agency: counter-publics aligning critical frames

Given frequent controversy of techno-market fixes, this has opened up greater opportunities to promote low-carbon, lower-energy alternatives. Yet there seemed a lacuna in social agency, i.e. a political force with the political will, collective capacities and necessary resources to implement solutions. Such an agency would need to link diverse socio-political forces much broader than the climate movement per se. So I looked back at various techno-market fixes, political strategies for promoting them, and multi-stakeholder strategies for undermining them, likewise various alternatives being promoted.

Alternative agendas have come from multi-stakeholder citizen-expert alliances. Together they have contested official knowledge-claims about benefits of the dominant innovation agenda. Such opposition has drawn on knowledge from socially excluded groups (e.g. service users, patients, low-income groups, small-scale producers, etc.), facilitated by NGOs and social movements. These ‘mobilised counter-publics’ have stimulated public controversy over dominant agendas, prevented public consent and counterposed alternative futures (as theorised by David Hess, Scott Frickel and colleagues).

Criticising dominant policy assumptions, such counter-publics have moreover highlighted the anti-democratic basis of technicized decision-making. Counter-publics identify ‘undone science’; they demand or generate resources for new knowledge which could serve a broad public benefit rather than private interests. They mobilise resources to fill the knowledge gap, sometimes for alternative solutions such as grassroots inclusive innovation. This involves solidaristic commoning, i.e. creating communities that defend commons or devise new ones. These forms contribute to eco-localisation agendas; they can build more enjoyable lives by creating lower energy forms of livelihoods and localising production-consumption circuits.

Counter-publics often emerge from social movements, whose participants bring diverse framings of a societal problem, e.g. environmental or health threats, socio-economic inequity, resource degradation, etc. Effective action depends on integrating all those issues for and through common action. As a feature of social movements, ‘frame-bridging’ aligns ‘two or more ideologically congruent but structurally unconnected frames regarding a particular issue or problem’ (as theorised by David Snow and Robert Benford).

In climate-fix controversies, alongside counter-expert critiques, opponents have framed false solutions in pejorative ways linking several issues. For example (see the Table):

climate-resilient agriculture with GM herbicide-tolerant crops as ‘corporate-smart greenwash’ which degrades the soil and monetizes Nature as financial capital;

biofuels as industrially produced ‘agrofuels’, whose land-use changes generate ‘a carbon-emissions time bomb’;

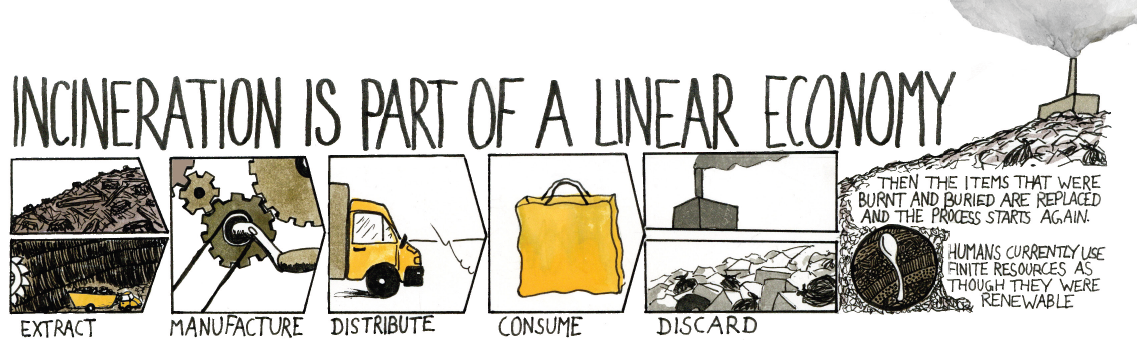

advanced waste treatments as ‘incineration in disguise’, and incineration generally as a ‘use-and-dispose linear economy’ wasting resources and harming nearby communities.

Such frame alignments have strengthened the basis for jointly undermining dominant agendas and advocating socially just, low-carbon alternative futures.

Climate Fix Controversies

| Techno-market fix | Climate promise | Pejorative frame from counter-publics | Opponents’ alternative |

| Climate-smart agriculture, eligible for carbon credits as an incentive | Carbon sequestration from no-till methods with GM herbicide–tolerant crops | ‘Corporate-smart greenwash’. ‘Monetizing Nature.’ |

‘Agroecology feeds the people and cools the earth.’

Food sovereignty. |

| 2nd – generation (advanced) biofuels from a mandatory market | Lower GHG emissions due to biomass (from ‘marginal land’) replacing fossil fuels | ‘Agrofuels: no cure for oil addiction’. ‘Carbon-emissions time bomb’ will come from land-use changes. |

Better public transport, mandatory fuel-efficiency, electric vehicles from renewable energy, etc. |

| Advanced Thermal Treatments (ATT) of waste with competitive subsidy | Waste-to-Energy conversion for high-value products such as vehicle fuel | ‘Incineration in disguise’. High-carbon ‘use-and-dispose linear economy’ wastes resources. | Circular economy through re-usable components, greater recycling and Materials Recovery Facilities |

| Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) with state subsidy. | Decarbonisation of fossil fuels, e.g. converting natural gas into hydrogen fuel. | CCS diverts resources and extends dependence on fossil fuels while awaiting an elusive fix. | Energy reductions and substitutes from truly renewable-energy. |

Academic-activist knowledge co-production: strategies for system diagnosis and change

For elaborating such strategies, a method has been academic-activist knowledge co-production, sometimes formalised as Participatory Action Research (PAR). Put simply, this means research with people rather than on them. PAR brings together researchers with practitioners, initially to identify practical problems and analytical questions that warrant joint research. Through PAR, participants should become empowered to play the role of change agents.

Environmental technofixes are generally capital-intensive innovations which supposedly bring eco-efficient solutions for decarbonisation or environmental protection more broadly. As counter-publics raised risk or sustainability issues, state bodies have framed them as direct biophysical effects of a product or technology. This frame has often channelled dissent into specialist issues, thus obscuring systemic drivers of harm. Regulatory procedures have evaluated potential effects through implicit normative assumptions as regards what potential effects may be relevant, acceptable or worse than some standard, as if these norms lay above politics.

Counter-publics have questioned such normative criteria, often disguised as ‘science’, thus extending public controversy to regulatory expertise. Moreover, they have highlighted how political-economic interests and institutional commitments drive the fix, while excluding beneficial alternatives. Through Participatory Action Research (PAR) methods, researchers and civil society partners have jointly deepened a systemic perspective on climate fixes, as a basis to undermine them more effectively and to counterpose alternative futures.

PAR has two levels: researchers intervene in stakeholders’ practices, at the same as they jointly intervene in a wider context. Through this collaborative relationship, participant groups can gain a better collective self-understanding of their problems and opportunities, as a basis for more effectively addressing them. This process can strengthen social agency for transformative aims. This book brings together many collective contributions, to be cherished as a collaborative process for lesson-drawing.

Overall the book elaborates a big picture of transformative mobilisations for climate justice. These need to combine four main elements: counter-publics, eco-localisation, grassroots innovation and solidaristic commoning. Together these can help build an effective social agency for system change. The big picture is elaborated through case studies such as GM crops, biofuels, waste incineration and Green New Deal agendas.

Les Levidow’s book, Beyond Climate Fixes: From Public Controversy to System Change will be published in spring 2023, https://bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/beyond-climate-fixes