Introduction

This paper is concerned with a reflexive account of the experience of both delivering and listening to presentations in an online environment and the changes that it has generated in terms of pedagogy. In particular, it considers the experience of the use of comics and associated videos as a means of delivering learning (whether this is framed within a conference environment or a more conventional on-campus teaching context). The starting point for this discussion is with the EASST/4S Conference as it was one of the first large-scale, on-line conferences attended by the author. The paper also reflects on some of the other conferences and workshops attended in a virtual format and with the subsequent early experience of on-line post-graduate teaching based on this early conference experience.

EASST was to be east but in reality it went everywhere

As the conference went virtual it, de facto, changed the rules of ‘engagement’ around the delivery of papers and how we communicate complex issues in, what could be seen as, a fractured environment. We rely on visual cues from those that we communicate with as a means of assessing understanding, but the flow of most conference presentations doesn’t allow for a fully interactive session due to time constraints. So, what if we could have the best of both worlds. Having a presentation but with the opportunity to answer questions in real time and within the various flows of the presentation.

There is an obvious challenge associated with a virtual conference. How do we ensure that there is sufficient engagement from those who attend the session? Is it enough to simply turn up and present a presentation over the appropriate conference platform? How do we get engagement from those in the audience and, perhaps more to the point, how do we gauge the effectiveness of that engagement when we are busy making a presentation? Finally, how do we design into conference presentations the potential for chance meetings in the virtual coffee breaks? These are things that we often take for granted when attending a conference as we are ‘in the room’ and have a range of visual cues that provide us with feedback. The key challenge of a virtual conference is, therefore, around the processes of engagement. It was as a means of trying to address that issue that we need to look to the work of Aristotle (Gallo 2017).

If we take on Aristotle’s’ arguments to heart, then the development of pathos is likely to be a key component of delivering in an online environment as it will allow for a greater sense of engagement from the audience with the presenter. It was an attempt to explore the notion of pathos that drove the underpinning pedagogical approach that is discussed here.

One of the approaches that the author had trialed before the conference was through the use of visualisation – initially as a means of storyboarding the academic content of slides – along with that of storytelling. The next logical step in that process was to develop ‘stories’ that were bespoke to the course being taught. An obvious extension of the visual storytelling approach was though the use of comics as a medium for communication and so a series of avatars were created to provide an additional commentary on the slide deck – usually as a means of provoking and questioning the speaker! The avatars were also embedded in a series of bespoke academic comics that were designed as the spine of the teaching approach. The purpose of attending the EASST/4S conference was to deliver an academic paper, but also to present a Making and Doing session on the use of those bespoke academic comics. The aim was to outline how comics theory could be used as a means of shaping the structure of a lecture, or presentation, and how the comics approach could be used to explain models and concepts in a concise manner. The approach was aimed at providing a more accessible means of delivering learning to those students who were studying in a second language. Then along came COVID-19 and the impetus changed considerably!

A comics-based approach to uncertainty

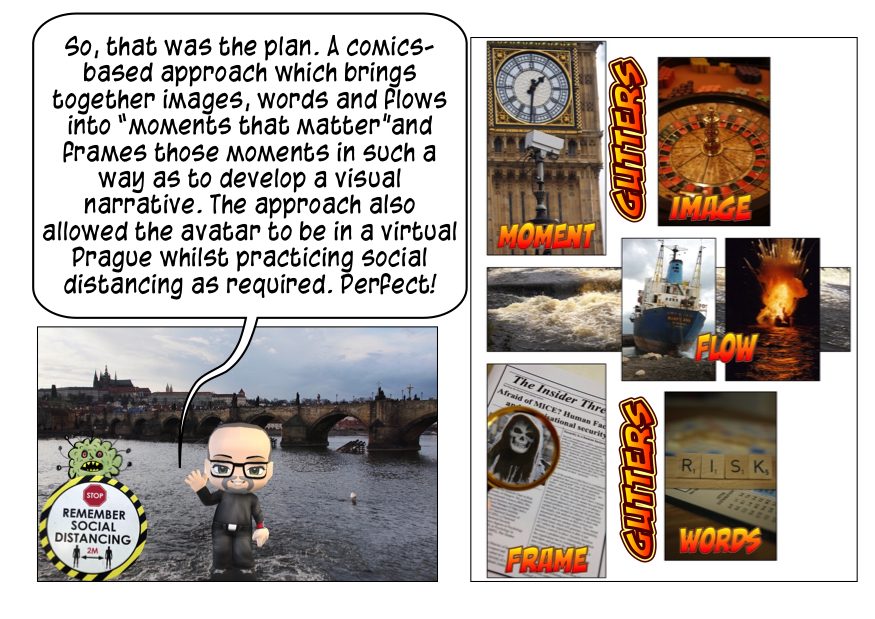

The theory of comics provides some insights into the ways that visual storytelling can be used as a means of communication (Potts 2013; Eisner 1996). The main elements of a comic-based approach are shown above and consists of images and words being used in a self-reinforcing way to enhance recall and understanding. There is a strong psychological basis for using the ways in which we process information via our cognitive short-cuts (heuristics) and we can use these processes as a means of developing understanding (through the visualisation of the narrative) and developing recall (Cohn 2013; Eisner 1996). These images and words are framed into discrete elements that are designed to develop meaning within the narrative structure (McCloud 1993). Each of these frames are linked together by the flows of the argument within the overall narrative, thereby allowing for the progression of ideas and concepts. The final element of comics theory relates to the gutters – the spaces between the frames. These can be seen as spaces of emergence in which additional issues can be raised or developed as a function of the interactions between frames to create moments that matter or to offer the potential for alternative interpretations within the narrative structure (see, for example, Berlatsky 2009). Taken together the comics approach provides for a means of providing insights into academic issues and developing insight and understanding. The COVID-19 changed that dynamic and led to a shift from the ‘static’ form of the comic to a more dynamic approach which required the animation of the avatar as a means of addressing the pathos element highlighted by Aristotle.

Animating the avatar and the emergence of Avatar TV

Right at the outset it needs to be stated that I had not produced a video lecture before COVID-19. This wasn’t a case of tapping into an existing skill set to turn conventional lecture material into video that could be delivered on-line. The need to pivot from a face-to-face form of delivery under the pandemic generated the impetus to use the software that produced the avatar to generate a talking avatar. That was then inserted into the slide deck and a script produced that allowed the avatar to take over as the presenter.

The delivery of the presentations took place in two discrete sessions – a formal academic panel and a Making and Doing session. The experience of both sessions was quite different. The panel session was a formal 15-minute presentation which was timed when producing the video. Questions were asked both within the session via the chat function but also at the end in a more traditional way. The impression was that the panel session went well and there appeared to be considerable engagement from the audience. The Making and Doing (M&D) session was a different experience. First of all, the author had limited experience of such a session as it appears to be unique to EASST/4S. Secondly, the time allocated for the session was 60 minutes and this generated logistical challenges in terms of breaking the presentation down into 15/20-minute blocks. The timing is important as 20 minutes appears to be the optimal time period for an online presentation. With hindsight, this introduced uncertainty into the timing as the questions occurred after each block. The level of engagement was such that the presentation came close to overrunning the time slot due to the extent of the questions from the audience in the period between the block delivery. With hindsight, it might have made more sense to deal with the M&D session by utilising a blended approach where the videos were made available prior to the session and this would have allowed the delegates to use the time available for the discussion. This would have been more effective but presupposes that the delegates would watch the videos prior to the session.

Concluding Comments

The move to an online format in which the avatar is given voice and put into a self-contained video lecture offers considerable benefits in terms of developing engagement (pathos) compared to a voice-over presentation and, possibly even an on-line, face-to-face lecture. Whilst the start-up cost of producing an avatar-led presentation are higher, if this is part of a wider approach to learning design then the material could be current for several years before it needs to be re-developed. In contrast, a ‘live’ on-line face-to-face session will incur the same time-related costs every time that it is delivered. In addition, the use of the avatar can generate the pathos that was highlighted earlier, especially if the avatar can be given a personality that is different to that of the lecturer. For those who are nervous about appearing ‘on-line’ in a video, the avatar-led approach offers some additional benefits. In terms of a conference presentation, the benefits are not as obvious and the main one is in terms of controlling the timing of the presentation to the timeslot that is allocated. It remains to be seen how this approach will develop in the future, but it could be argued that our institutions will change as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic and we will need to explore new, more student-centred approaches to learning and teaching as a consequence. This is a first step in a brave new (avatar-led) world.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Will Varner and Carl Potts of the New York School of Visual Arts and Alan Irwin from Copenhagen Business School for comments on the underpinning construction of the comics approach which is described in this paper. Needless to say, all errors of omission or commission remain those of the author, although a certain avatar may also bear some responsibility as well.

Bibliography

Berlatsky, Eric. 2009. ‘Lost in the Gutter: Within and Between Frames in Narrative and Narrative Theory’, Narrative, 17: 162-87.

Cohn, N. . 2013. The visual language of comics. Introduction to the structure and cognition of sequential images (Bloomsbury Academic: London).

Eisner, W. 1996. Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative (W.W. Norton & Company Ltd.: New York, NY).

Gallo, C. . 2017. Talk like TED. The 9 public speaking secrrets of the world’s top minds. (Pan Books: London).

McCloud, S. 1993. Understanding Comics. The Invisible Art (HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY).

Potts, C. 2013. The DC Guide to Creating Comics. Inside the art of visual storytelling (Watson-Guptill Publications: New York, NY).