by Roos Hopman, Tahani Nadim, Lisette Jong

Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 5-6 June 2023

Why are natural history museums digitizing millions of specimens? And why is there such an emphasis on doing this speedily? Who benefits from speeding up the digitization of collections, and what might the focus on speed obscure? In other words, what might be learned about the politics of speed when examining collection digitization, and the assumptions about the digital? These were some of the questions that led Roos Hopman and Tahani Nadim, organizers of a recent workshop, to invite scholars from different institutions to join them for discussions at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, where they have been co-conducting research on the large-scale digitization of collections since 2021. In the workshop titled “Thinking speed: stories, promises and practices of digitization”, funded by the Berlin University Alliance in the context of the “Museums & Society: Mapping the Social” project, the organizers wanted to facilitate the articulation of shared concerns around speed, the digital and attendant issues. The workshop brought together scholars interested in collectively thinking (with) speed: Where does speed pop up in- and outside of-natural history museums, what does it do in these contexts, how can it be made sense of? It was important to the organizers that discussions were situated and responsive to the specific material and discursive spaces of the museum. Hence we visited one of the museum’s exhibitions, wandered around its basement, had drinks in its gardens, made a visit to the non-public collections, and got our hands dusty in one of the museum’s libraries.

On the first afternoon of the workshop Roos and Tahani introduced the themes of speed and digitization to the group by paying a visit to the digitize! exhibition, where, using a conveyor belt system, “scan operators” have been publicly mass-digitizing insects since autumn 2021. Examining this human-insect-machine assemblage offered an apt prompt for questions connecting speed, digitization processes, and natural history collections. On display are not only the machine and insects but also human workers who gently place each insect onto the conveyor belt, and return it to its drawer after it completes its trip through the digital photography station. In this arrangement, digitization means taking high-resolution digital images of the specimens and accompanying labels. But it also entails an additional set of processes such as cleaning, and rehousing specimens to new boxes. A large wall of screens, which shows the number of insects per unit of time that are “processed”, forms the background to this operation. Here, speed figures as a quantifiable measure of success. This raised questions about speed becoming an aim in itself because it appears so “doable”. We also discussed how insects, being relatively small yet so numerous in the museum, were particularly suitable for such a spectacle of digitization and its enactments of speed.

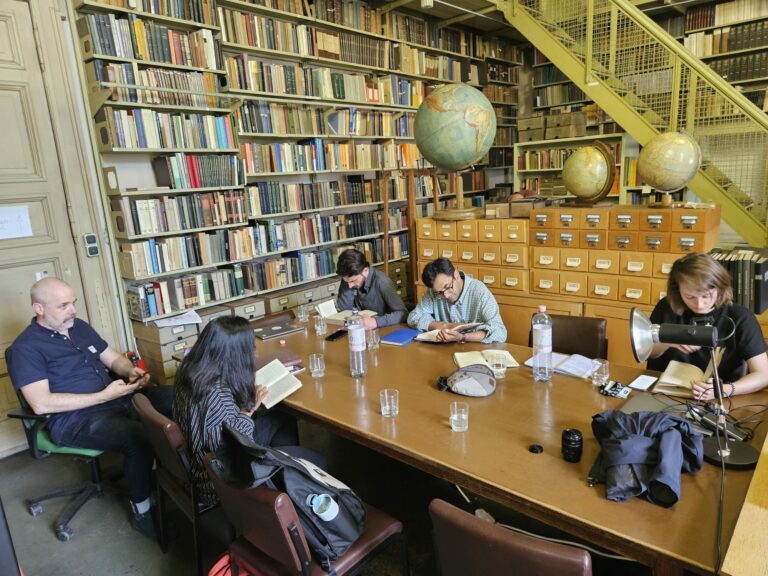

The participants then moved to the paleontological library, where time seemed to slow down to a geological pace. Reams and reams of mostly old (and some new) books (mainly from the 19th century), manuscripts, journals and leather-bound volumes lined its walls, index card catalogues nestled amidst shelves, and old globes hovered on top of the wooden cabinet that formed the backdrop to our gathering. After a first round of introductions, Tahani and Roos invited the participants to explore the library, browse its contents and select a passage that resonated with them and/or with the workshop’s topics. As we re-assembled around our meeting table, participants each read their text passage out loud and provided an explanation of why they chose it. This exercise brought up expected and unexpected associations relating to the meaning of ‘data’ in “the Data of geochemistry”, to quibbling between geologists on the validity of scientific descriptions, and to the economy of time in scientific surveys of British India. The passages sparked conversation about current categorization practices and the politics of digitization, offering a stark reminder of the colonial legacies in specimen collecting and field research. We ended the day in the museum’s so-called “Zaubergarten” where, magically, a red fox (Vulpes vulpes, Linnaeus, 1758) appeared.

The morning of the second day was centered around short inputs by each of the nine participants. Everyone had been asked to relate to the concept of speed, to present how it appears in their work, and how they make sense of it. Prior to the workshop, the organizers had sorted these contributions into three themes: 1. Data, governance, instantaneity; 2. Collections, datafication, urgency; and 3. Technology, innovation, desire. Contributions in the first session demonstrated how speed is performed “from above”, for example through a “live” dashboard tracking the processing of governmental reports in Bangalore (Nafis Hasan), through the promise of “anytime/anywhere” identification in the context of Aadhaar, India’s national biometric database (Vijayanka Nair), or with “smart” traffic lights in Vienna (Pouya Sepehr). In the second session, the focus shifted towards natural history specimens (Lisette Jong and Roos Hopman) and biodiversity data preserved in cryobanks (Veit Braun).

In these inputs the shared sense of urgency evoked around the anticipated extinction of species legitimized speed. In the final session we took a pause to examine the problem-space which poses digitization as a solution (Andrew Gilbert), the promissory narratives around new technologies through the pace of obsolescence and “temporal drag” (Tahani Nadim), and the assumed speed of algorithmic processing (Ildikó Zonga Plájás).

After lunch we went on an excursion to the museum’s malacology (snails, slugs, clams, cephalopods) collection to look for speed in situ. There, we were welcomed by Nora Lengte-Maaß and Margot Belot, who have been overseeing efforts to digitize its estimated seven million snail shells since 2020. Explaining the technologies used to digitize this collection to us, they addressed questions and issues they face inventorizing and photographing (sometimes extremely tiny) specimens en masse. During this excursion surprising connections to our previous discussions emerged. We learnt that speed is measured and tracked through numbers of specimens digitized and that progress is mapped via a “digital dashboard” resembling the dashboard displays we find in most cars. Finally, we noted how the project of speeding up introduced novel ways of ordering the museum’s organizational processes, introducing notions such as “workflows” and “storytelling” into collection work.

In our discussions, key questions were raised about speed as a value within contexts which strive for continuous optimization, such as in the case of automated traffic lights (Pouya Sepehr) or digital IDs (Vijayanka Nair). These and other cases highlighted the relation between space and speed: since speed and velocity, as Lisette Jong reminded us, are physical properties describing the rate at which objects cover distance. Our case studies (and excursions) thus prompted consideration of how speed acts upon our fields and sites. Such consideration also encompasses an assessment of the epistemic space through which questions of speed become legible (and relevant). Here it was interesting to note that many of us reflected on speed through colonial contexts, rather than contemporary technologies.

However, each participant grappled with very different iterations of speed. Speed for example emerged as a measure of efficiency and productivity in bureaucratic practices, as a sense of urgency in accounts of biodiversity loss, and as a heuristic to think with. Speed was also unsettled in different ways: for example, by following those activities of bureaucrats and scan operators that cannot be captured in a workflow (and thus escape or, indeed, refuse optimization), by observing the long meetings and discussions that precede the training of algorithms, or by attending to those machines that are considered to no longer be up to speed. It became apparent that when we were discussing speed, we readily equated it with being fast. But whereas speed is always about movement, about motion, it does not necessarily mean fast movement. This brought us to critiquing the need for speed: we questioned it, and wondered about alternatives for speed. While our ethnographic cases demonstrated how speeding up was obscuring particular kinds of labor and histories, we also wondered whether we might think of speed in “less dystopian” ways, as our participant Andrew Gilbert put it. Rather than trying to reify “speed” as a comprehensible object of research, our final discussions arrived at the theme of temporality, more generally. Our objects – frozen tissue samples (Veit Braun), obsolete machines (Tahani Nadim), colonial handbooks (Nafis Hasan), simian bones (Lisette Jong) – articulate very different notions of time (biological, social, bureaucratic) and, embedded in practices, can disrupt the normative organization of historical time (its proper workflow, if you will).

This workshop gathered nine people interested in engaging with the notion of speed and in thinking and collaborating with one another beyond the workshop. Some of the participants will submit a panel for the 2024 joint 4S/EASST Conference, and another workshop on the topic of speed/temporality and data will be planned for next year. In these future meetings we also want to explore more creative and interactive (digital?) formats. (Producing an alternative dashboard was suggested.) We very much welcome others who want to join forces to think these topics through. Please reach out to us!

Author Biographies

Roos Hopman, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Roos Hopman is a researcher between the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, where she studies data collection and digitization practices as part of the BUA funded ‘Museums and Society’ project. Besides providing a fascinating research site, working at the natural history museum has further deepened her affection for and interest in snails and other gooey creatures. Previously, she studied forensic genetic technologies and the surfacing of race in them. She is also a recent addition to the EASST Review editorial team.

Tahani Nadim, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Tahani Nadim is Junior Professor for Socio-Cultural Anthropology in a joint appointment between the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and the Department for European Ethnology at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. She co-heads the interdisciplinary Center for the Humanities of Nature at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and runs the experimental research unit Bureau for Troubles in which she collaborates with artists and curators. Her work focuses on the datafication and digitization of nature and, more recently, the politics of conservation.

Lisette Jong, University of Amsterdam

Lisette Jong works at the Anthropology Department of the University of Amsterdam. Her research into the entanglements of natural history and colonialism is part of the project ‘Pressing Matter: Ownership, Value and the Question of Colonial Heritage in Museums’ funded by the Dutch National Science Agenda (NWO). Her research investigates non-human primate remains that arrived in natural history museums and university collections in the Netherlands through colonial networks and focuses on historical and present-day concerns around extinction and human-animal boundaries in scientific and museum practices.