22nd of March, 2022 – “Paissii Hilendarski” University of Plovdiv, Compass Conference Hall1

The Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev has described the war in Ukraine as the end of more than 30 years of “peace in Europe” after the Cold War and a dangerous beginning of a new era, which changes the world in which Europeans have lived so far. To discuss current events, a round table was organized by the Jean Monnet Center of Excellence at “Paisii Hilendarski” University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria, with teachers, students and members of the public participating in person and online. The Center is part of a European network that brings together expertise of researchers to develop interdisciplinary research and training in European studies.

The round table discussed the war in Ukraine in three panels, each addressing the areas of our center’s specialization – 1) Humanitarian crisis, welfare, social and youth policies in the context of European values and identity; 2) Democracy, law and the rule of law, including the prospects for EU enlargement; and 3) Science, Technology and Innovation in the context of military opposition”. The text below briefly outlines the first two panels, to focus in more details on the last panel. The members of Science, Technology, and Innovation unit at the university’s Department of Applied and Institutional Sociology contributed to the panel.

In the first panel on “Humanitarian crisis, social and youth policies in the context of European values and identity” the participants Assoc. Prof. Dr. Abel Polese (Dublin City University, Ireland) and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Irina Popravko (Tomsk State University, Russia) presented their insights “from within” the humanitarian crisis and its dimensions. Abel was leading several research projects in Ukraine and flew to Kyiv on February 23. A day later he had to escape by car under the bombs to Romania with “his children, two cats, his ex-wife and her husband”. Having already published his bitter account from the war’s first days, he focused on the disturbing positions spreading already in some EC countries, one blaming the expansion of NATO that pushed Putin to invade, and the other hoping everything to settle down once Ukraine surrendered. He argued in detail why such views are incompatible and in deep contradiction with the core European values he has studied extensively and which are at the heart of the EU project. He discussed how these values should be reshaped in the future after being practically inactive before and immediately after the war. He also pointed out the importance of having a critical mind that allows to check what comes to you in the form of information, rather than dogmatically believing on what is presented as “absolute truth”.

Irina Popravko reflected on the war from an anthropological perspective. She pointed out that the first visible effect of the war is splitting Russian society into two parts, those who are supporting Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, and those who are not. This split happened not only in public sphere, but also in families, professional communities, and so on. It is possible to talk about a “society/community of trauma”, because most of them define the war as a milestone that divided their lives ‘before’ and ‘after’ February 24th. Starting from this there are problems with different kinds of social identity people have, such as national, local, and professional (e.g. social and humanitarian researchers, teachers, journalists). Another preliminary effect of the war is self-descriptions of an ‘antiwar’ part of Russian society in terms of collective responsibility: what we did not do, or did not do enough to allow Putin’s regime to start the war. Searching for the answers and trying to conceptualize the new reality some of Russian anthropologists have started to re-read Hannah Arendt. She pointed as the main problem of Russian society its passive, indirect complicity in Putin’s actions. Traumatized Russian society, especially older people who lived during the Soviet era, is forever marked by the war, and their lives are based more on survival than living.

Their views were complemented by a speech of a famous public figure, Manol Peykov, who manages one of Bulgaria’s largest publishing houses and is owner of two printing houses. He presented his civic initiative in support of Ukraine and the refugees from the war. During the first seven days he actively translated important texts, mainly from the Russian-language media by journalists and researchers, as well as stories from the actual situation in Ukraine. This activity, against the background of the limited coverage of events in the Bulgarian media, gained him followers at his personal Facebook profile which gradually became an information center about the war in Ukraine and part of other practical activities in support of Ukraine: donations of medicine, essential products, materials and other items sent to regions such as Odessa, Kharkiv, Nikolaev. He soon provided his personal bank account for monetary donations to make it easier for people who are willing to help but do not have the physical time to donate products at crisis centers. Within 10 days, Mr. Peykov’s bank account received about BGN 40,000 from donors (about 20 000 euro): “This bound me with careful and accurate accountability, because after all, these people give this money to me, not to a large institution, because they associate my face with a person who is concerned”, explains Manol Peykov. He used the funds to support a group of Ukrainian students in Bulgarian universities who after the war could not receive funds from their relatives in Ukraine, for renovation of kindergartens for the children of Ukrainian refugees in Plovdiv, etc. He pointed that “at one point I was in a whirlwind by the logic that doing something meaningful leads to something more meaningful, and so on. I think this was the way to change the world for the better since we cannot hope that someone from above will start things, but we are the ones who should do it!” He explained the popularity of such personal initiatives in light of the inability of institutions to rapidly respond to what is happening: people are looking for someone they trust to channel their energy and contributions.

The journalist Veselin Stoynev outlined a “dark picture” of the effects of the war in Ukraine on Bulgarian society, which seems divided in two relatively equal camps. The first comprises nostalgic people turned to the past, for whom the results of the post-communist transition are not considered fair and who therefore do not accept the newly established order and its values, institutions and projects for the future. The other camp includes people who are against the Russian invasion, who take position and provide assistance to Ukraine. This part of society is less noisy, while the pro-Russian camp expresses its positions loudly, often claiming that the military conflict is a ‘staged play’ and that everything is a media product. Stoynev claimed that Russian propaganda finds its way to the “other” Bulgaria effectively and professionally, directing focused information flows to targeted groups via social networks and special websites. According to Stoynev, the Bulgarian media also contributed to this split in society, failing to fulfill their role as a responsible public mediator. They often hide behind the principle of “presenting all points of view” providing a platform to reactionary politicians whose ideas are against the interests of the country and its membership in EU.

The second panel on “Democracy, law and the rule of law, including prospects for EU enlargement, consolidation and positioning as a global factor for the stability” was opened by Prof. Georgi Dimitrov from University of Sofia. By analyzing the process of preparation and membership of Bulgaria in the EU, as well as Romania, Hungary and Poland, he defended the thesis that there is no “fast path to EU membership”. The Union cannot influence the local policies of a Member State, so the Europeanization of the candidate country must be successfully completed before it can join the EU. Ukraine needs to be admitted to the EU, but it will not be able to cope on its own and must receive a comprehensive strategic program with adequate funding to prepare for membership. Prof. Dr. Irena Ilieva, Head of the Institute of State and Law at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Dimitar Angelov, PhD candidate, spoke about the special status of “asylum seekers” from the war as different from the status of the “refugee” and assessed the reactions of the institutions in the EU and the member states. The panel discussed some persistent lacunas in legal and policy framework of European integration in the field of health, that became apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic and related this to the existence of similar gaps in the field of defense.

The third panel focused on “Science, technology and innovation in the context of the war in Ukraine” in two particular areas: 1) the energy and technology issues between EU and Russia in the context of sanctions, and 2) limits of the geopolitical frame of reasoning.

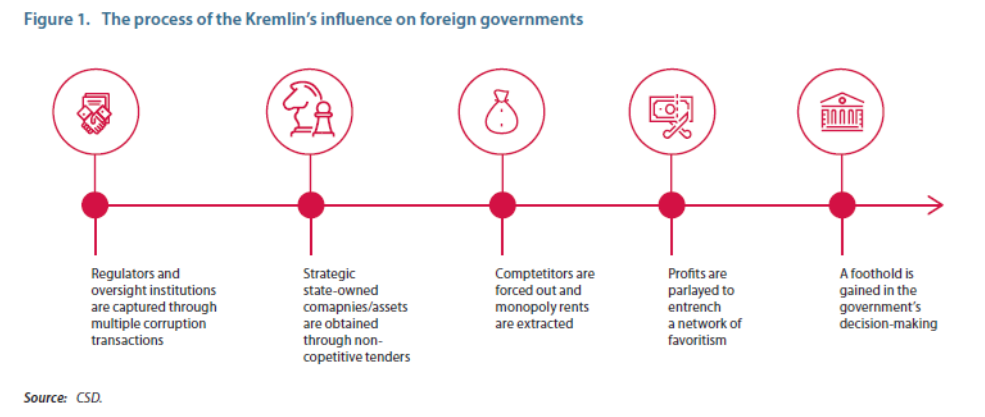

In the first area, papers were presented by Dr. Todor Galev and Konstanza Rangelova, researchers at the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD), a Bulgarian think tank. Their reports have been based on a so-called Kremlin Playbook, a series of CSD analyzes of the ways in which Russia exerts political and economic influence in Europe. The basic scheme of Russia’s economic influence is the presence of Russian businesses or businesses that are completely dependent on Russia in EU countries (see Figure 1 below). These are not only local companies with legal ties to Russian companies, but also those having a so-called indirect economic footprint. For example, Lukoil Bulgaria – wholly owned by Russia, possesses plants and headquarters in the city of Burgas which is the only site in Bulgaria of such national importance, guarded by armed guards from Russia who are in a sense completely independent of the Bulgarian army or police.

Todor Galev provided data about the extremely high degree of integration of the Russian financial and banking system into the financial and banking system of Europe, where Austria, Germany and Italy serve as the main channels through which Russian capital enters the European economy. EU banks’ exposure to Russia by the end of 2019 is also substantial (almost 130 billion of euro), although it is almost half as much compared to 2014 (before the Russian invasion in Crimea). He also shared his observations and initial conclusions about the impact of sanctions on Russia’s science and technology policy and the later ‘hybrid’ response.

The technological policy of the Russian Federation, even since the Soviet era, is based on two main postulates: own development of key technologies through re-engineering and less original innovations. Particularly in the field of energy extraction the partnership with Western companies for access to high technologies dominates. In the field of armaments there is a combination of the use of own technologies and the purchase of key technologies and / or an elemental base from Western companies. Consequently, Todor Galev outlined the effects of Western sanctions on Russia after February 24th on aviation, bank sector, heavy industry and machine building and provided details on Western companies in each sector differentiating them in four groups (Withdrawal of all activities, Suspension, Reduction of reliability, Economic cooperation in opposition of sanctions). The most serious effects of sanctions on Russian technology include the breakdown of supply chains (especially of materials and components already stretched by Covid 19 pandemics), restriction of R&D investment, brain-drain, isolation of Russian scientific communities from their Western partners and significant delays in many research projects, unemployment of intermediate and highly qualified staff.

The Russian ‘hybrid response’ to this are ‘counter-sanctions’, strengthening of disinformation and propaganda, belittling the effect of Western sanctions and claiming stronger effect of ‘counter-sanctions’, mobilizing ‘friendly’ public opinion abroad, increase of the efforts in illicit (illegitimate) financing. Galev expected that Russia will further use the instruments for political and economic influence in EU by showing support for pro-Russian parties and leaders, locking in defense cooperation, continuous reliance on spy networks and security services, as well as benefiting from managerial deficits (including corruption) in some EU countries to influence national policies.

Konstanza Rangelova talked about the energy and climate risks of the war in Ukraine and its effect on the EU Green Deal. She pointed out that large Russian companies such as Gazprom and Lukoil, through their influence on EU institutions and businesses, are building informal networks that penetrate deep into the European economy. These networks impose a vicious circle that intensifies corrupt practices and directly imposes Russian political interests in exchange for business opportunities for their local partners. In this way, Russia is increasingly interfering in politics and strategic decision-making in Europe.

In addition to these informal networks, the main weapon of intervention is the income Russia receives in foreign currency from the sale of oil and gas. These revenues are huge – at current prices the daily income is almost 1 billion dollars a day, of which almost 400 million goes directly to the Russian government in the form of taxes and fees. These revenues largely minimize the effect of the sanctions imposed so far and make EU a major financial donor, given the sanctions. Simply talking about new sanctions against Russia increases the price of its oil and gas, and thus its revenues. The most dependent on Russian oil are Germany, Poland and the Netherlands, and in absolute terms Germany and the Netherlands are the major importers of Russian oil. Other countries such as Finland, Slovakia, Lithuania, Bulgaria and Hungary are also heavily dependent on it.

The Figure 2 below shows the main energy companies as agents through which Russia can impose its interest in Europe, where the danger is directly dependent on the proximity of each of these companies with Russia and the corresponding profits for both countries.

So, if at political level the EU is talking about energy diversification, in reality on the ground there is a deepening of the process of integration and mutual penetration between EU and Russia. In 2020-2021 Rosneft increased its shares in a large number of companies engaged in oil transportation in Germany, and in 2022 the company is processing the largest share of oil in Germany through its subsidiaries Bayernoil, Raffinerie GmbH, and MiRO. Oil traders are also important because they also rely on close relations within Russian companies, most of which are based in Switzerland and have historically gained experience in avoiding various types of sanctions, not just with Russia. Similarly, in recent years, instead of declining, the EU’s dependence on Russian gas has increased, with some countries relying on 75% or more.

Discussing possible EU responses to the energy dependence on Russia, Rangelova stressed the importance of developing a comprehensive strategy that includes immediate measures to be taken together with measures in the medium and long term. Short-term measures should concentrate on putting energy security back in the energy policies’ mix, making binding gas solidarity agreements between EU Member States, a EU Common Gas Purchasing Mechanism, reducing excise and VAT duties on natural gas, integrating Ukraine in European gas and hydrogen markets, and cancelling large-scale Russia-led energy projects such as nuclear power plants and natural gas infrastructures. In medium term Europe should renew domestic gas production in Groningen and Denmark, remove take-or-pay clauses on existing contracts with Gazprom, accelerate strategic interconnectors and gas storage projects, further develop green hydrogen technology, expanding offshore wind and battery storage as replacement of natural gas in power generation, and limit the penetration of Russian capital in strategic markets. Long-term solutions are electrification based on renewable energy sources, improved integration and liberalization of natural gas and power markets in Europe, renovation programs to reduce energy consumption, strategic alignment of U.S. and EU energy and climate security policy, investments of EU and U.S. in regional infrastructure projects and improving the security of supply, diversification and de-carbonization.

Prof. Ivo Hristov (Sociology of Law) presented a geopolitical account on the main trends in the development of worlds’ powers, entitled “On the eve of a new era”. According to him, current events mark the end of the cycle after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in which a unipolar model dominated by the United States was imposed. He suggests that the geopolitical model of the world distribution of power is being reshaped in cycles of about 20-25 years. As such, the crisis is not a temporary violation of the existing status quo, but is based on a qualitative change in the status quo as such.

He outlined the following key characteristics of the new geopolitical circumstances: 1) De-globalisation, which could be characterized also by the circumstances surrounding the outbreak of the global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the cessation of movement between countries of people, goods and capital. 2) Following de-globalization, the new distribution of power will focus on several economic and military centers, each considered as regional alliance with a population of 300-500 million people.

For the past 30 years or so, the world has been built around its dependence on the industrial north, namely United States and the Euro-Atlantic core. This model was guided by several rules: the dollar as the world‘s reserve currency; China as world‘s factory for export to the ‘western’ industrial center; and Russia, the former territories of USSR, and the Middle East – as world raw material appendage. The emerging geopolitical blocs will replace the current unipolar model and will be formed in relation to each other as several military, economic and political autarkies that will exist relatively independently. Tentatively they are the following:

- The US and the EU, as Europeans need US raw materials and industry.

- China and Russia, which will be drawn away from China‘s economic mentoring as a result of „Western“ isolation.

- Arab-Muslim with dominance probably of Turkey, Egypt or Saudi Arabia

- East Asian bloc – Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Australia. In this scheme India can be either a stand-alone bloc or part of the East Asian bloc.

According to Histrov, the problem for Bulgaria is that it is located around the borders of the respective emerging blocs, i.e. where the „frictions“ between the „geopolitical plates“ take place. The Bulgarian state and political elite which lack vision in the emerging geopolitical circumstances and is generally unable to lead the country, is going through economic and demographic crises. Hence Bulgaria is completely unable to adequately respond to the upcoming geopolitical shifts. Globally, the post-war institutions that emerged after World War II – such as the United Nations and others, and which are based on a certain power structure that has sustained the globalization process so far, are expected to be nullified.

In their presentation “Geopolitics as a “style of thinking”: modern legacies and current limitations” Prof. Ivan Tchalakov (Sociology of S&T) and doctoral student Bilyana Mileva draw from the obvious incompatibility between the tragic events of the war in Ukraine which we witnessed from the media, refugee stories and immediate participants on the one hand and geopolitical concepts of various analysts on the other hand explaining in the same media how Putin had no choice because Ukraine is subordinate to the United States and NATO, etc. As researchers in the field of STS, they observe how the classical sociological conception of science has given way to an understanding of the various contemporary problems in which modern science and technology are involved. Today we are much freer to critically examine the theses of expert scientists, while they argue that geopolitics seems to have remained in a way of thinking whose foundations are in the second half of the 19th century.

They turn to the book Geopolitics, in which Colin Flint states that geopolitics is attractive because of “its apparent ability to explain in simple terms a complex and, for some, threatening and uncertain world. In offering simple explanations geopolitics can be reassuring, providing one-dimensional explanations and solutions. Such explanations are reassuring because they create the illusion of being able to know and hence to understand the world.” These simple explanations give political elites a comparative horizon on the basis of which to plan their political actions. In fact, since its very beginning in the late 19th century, geopolitics was made by political elites and their experts, and not so much by the academic community of geographers. It was not until the end of the Cold War that “critical geopolitics” emerged as an academic discipline that began to criticize this approach. As such, it is important to keep the possibility of another geopolitics, which does not reduce but recognizes the complexity of the world and hence no longer imposes the point of view of one or another (political) actor and their order, but works as a framework for distancing from the obvious.

- Regarding the war in Ukraine and the period immediately preceding it, the characteristic features of classical geopolitics are particularly evident in the works of Alexander Dugin as one of the ideologues of the new Russian expansion. Analyzing one of his extensive interviews on Bulgarian TV channel in 2017, Tchalakov and Mileva find the typical simplified and reduced understanding of our complex world:

- eternal conflict between the Eurasian continent and the Atlantic powers with its dynamics, where at the end of the Cold War Russia briefly “lost its identity” as a Eurasian power

- tension between the peoples with their lasting and “eternal” features (culture, religion, race – e.g. “Slavic affiliation”) on the one hand, and the political elites who may change their orientation, sometimes against the will of the “people”

- eternal and unchanging characteristics of peoples, as well as their historical memory, determining the lasting relationship of love and gratitude between them, as well as who their “real enemy” is

- asymmetry between countries from the “periphery” that could choose in the opposition between West and East and ‘core

The insolvency of this simplistic view of the world is obvious and the critique summarized by Colin Flint in the above-mentioned book, is fully applicable here too. First of all, Dugin speaks from the privileged position of an expert, belonging to the ruling political elite – well, not the Atlantic and Protestant, but the Russian and Orthodox elites. Secondly, he presents a typically masculine position of an empowered white man who “knows everything” and has the right to provide classifications and make distinctions. Thirdly, this “empowered white adult Eurasian” is applying the scientific method of geopolitics, through which he builds an “objective” historical theory of what is happening in the world, and which sets and justifies the relevant foreign policy. Fourth, precisely because of their objectivity and appeal to be scientific, but also because of their simplicity similar to the laws of mechanics, these easy-to-understand and simple schemes aim to gain public support. Last but not least, geopolitics speaks of large-scale beings – “Orthodoxy”, “Russia”, “Eurasia”, which are presented as objective facts while these are labels and constructions used by small groups of people in power (who control significant material, human and communication resources) to impose their private interests.

As such, Dugin presents, in post-modernist language, an ideological meta-narrative. But this story can by no means claim universality, much less “objectivity”. In fact, geopolitics is a resource for building actor-networks where it not possible to draw a firm distinction between the global, national and local levels. Therefore, this “wholesale” thinking creates a certain deficit of “embodied” perspective and “situational knowledge”, of talking about real people in real places, i.e. there is a lack of purely human stories of broken destinies, lost lives and sacrifices – something that classic geopolitical analysts like Dugin cannot (and may not want to!) to admit in their analysis.

Consequently, Tchalakov and Mileva turn to Bruno Latour with his concept of “Gaia”, i.e. not the Earth as a globe, an abstract map, but as a thin layer (crust) capable of sustaining life, which is in fact a system without scale. Latour argues that we cannot separate micro from macro level, just as we cannot separate microorganisms (useful or harmful) from the human body and from other animals. After Lovelock, Latour speaks of Gaia that is suitable for life (habitation) and in which all our interactions take place. As such, we cannot really go back to the old and traditional way of life, but we also cannot go back to the new one – the idea of the Earth as a planet, because it is impossible to fit the interpretations of different actors into what our planet is, and what our direction of development is. Thus, Gaia is a complex and ambiguous entity, very different from that of the old geography, through which to unravel the ethical, political, theological and scientific aspects of the already outdated notion of nature. And in fact, what we have to do and where we have to start is the relationship with the person next to us, the one we argue with or the one we are friends with.

The authors are therefore convinced that the geographical side of geopolitics will sooner or later become “meaningless”, in the same way that the idea of the existence of “eternal” racial, religious or cultural characteristics of peoples has lost its scientific basis. And that even if they matter, geographical, religious, cultural and racial factors are only part of a much more complex picture of the world, in which they are often of limited importance. However, the danger remains – in the event of educational failures and when growing masses of people refuse to think critically, educate themselves and question the suggestions offered to them, geopolitical schemes will remain popular and convincing, and thus serve as an excuse for openly misanthropic and criminal policies.

1 Our tanks to Petar Parapanov, Vanesa Laleva and Zoro Zorov, B.A. Students at the Department of Applied and Institutional Sociology, University of Plovdiv who helped in transcribing the talks at the Round Table. We would like to thank also Dr. Dimiter Panchev for English editing.

References

Flint, C. (2017) Introduction to geopolitics, Third edition. | Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.