In September 2020, I and my collaborator Larry Au (Columbia University) received a grant from the Social Science Research Council’s (SSRC) “Rapid-Response Grant on Covid-19 and the Social Sciences” for our project “Viral Agnotology: Covid-19 Denialism amidst the pandemic in Brazil, the United Kingdom and the United States”. In total, 62 projects received funding from the SSRC, on topics touching on all aspects of the social, economic, political, and cultural impact of Covid-19. The aim of grant is to help put social scientists in conversation with the global scientific dialogue on the pandemic’s directions and consequences, and to help spur reflection on how social science can be useful to improve the preparedness of society for future pandemics.

Our project is ongoing, but I gladly introduce our project to readers of the EASST Review to help stimulate the interest of our colleagues on the topic of Covid-19 denialism, and point to ways in which STS as a field can be useful in thinking through this highly politicized topic.

Motivations for the project

By Covid-19 denialism, we refer to a broad range of doubt and skepticism expressed over the existence, severity, and need for public health interventions to mitigate and contain the further spread of SARS-CoV-2. This ranges from anti-lockdown protests, conspiracy theories that Covid-19 is a hoax, and skepticism over the need to wear a mask despite expert support for masking. Curiously, even as the pandemic unfolded and as evidence of Covid-19’s dangers piled up, major proponents of Covid-19 denialism continued to downplay the seriousness of the situation. The contentious encounter between expert discourses and Covid-19 denialism was particularly visible in Brazil, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Jasanoff et al. (2021) in a recent comprehensive report published on the Covid-19 responses in 21 countries, categorized these three countries as “Chaos Countries” because of the inability of state and society to cohere around effective strategies to mitigate and contain Covid-19.

Researchers in the past have looked to social indicators as level of education, the development of science and technology in society, and public trust on science as factors that contribute to scientific illiteracy. But these factors clearly do not explain the presence of Covid-19 denialism in many parts of the developed and developing world. Other analysts have pointed to the advent of the digital age and unregulated social media, as sources of disinformation and misinformation. While this is undoubtedly a factor in giving rise to Covid-19 denialism, exposure to fringe sources of information occurs in a wide range of societies, yet not all have succumbed to paralysis in rallying support for public health interventions. Further complicating this is the spread of misinformation by political leaders and heads of state.

Studying a topic such as ignorance is tricky, especially in such polarizing times. Nonetheless, our interdisciplinary backgrounds in STS provides us with approaches to broach this subject with care. Our analysis is based on three steps: (1) contextualize the discourses of Covid-19 denialism addressed to specific topic dimensions of the pandemic, (2) trace the discourses of denialism over time, and (3) see how these framings of the crisis are taken up by different audiences. This will enable us to further understand how the frames of denialism are taken up in different societies and how these discourses account for a fast unfolding crisis.

Beginnings of a conceptual framework

Our theoretical starting point comes from Proctor’s (2008) discussion of agnotology. As Proctor writes, “we need to think about the conscious, unconscious, and structural production of ignorance, its diverse causes and conformations, whether brought about by neglect, forgetfulness, myopia, extinction, secrecy, or suppression. The point is to question the naturalness of ignorance, its causes and its distribution” (10). Covid-19 denialism arises from actors behaving consciously with mal-intent, as a byproduct of institutional arrangements and technological infrastructures, as well as the unintended consequences of well-meaning policies aimed at combatting the pandemic. It is this latter factor that we focus on.

Brooklyn, New York City, USA. (Source: The Atlantic by Go Nakamura/Getty Images)

We also draw on Eyal’s (2019) recent book on the “crisis of expertise”. As Eyal helpfully notes, there are many parts of science that the public do not question in their day to day lives, like theoretical physics or civil engineering. But when science is asked to make policy decisions that have direct implications on people’s lives, then this policy-relevant science becomes the subject of debate and skepticism. Public health as a scientific discipline has life and death implications, particularly during the pandemic, making it perhaps the most controversial part of science during these troubled times. Covid-19 denialism, should therefore be understood in relation to public health expertise.

Furthermore, Jasanoff (2007) demonstrates that such public deliberations over evidence and knowledge can be studied cross-nationally from the lens of sociotechnical imaginaries, as how a particular society understands the emerging public health crisis will depend on relationships between experts and expertise with social, political, and economic structures. By taking up the idea of sociotechnical imaginaries, we hope to show how dominant forms of pathogenic imaginaries, as seen in public health expertise, contain blind spots that make them susceptible to populist challenges. These blind spots enable insurgent pathogenic imaginaries to mutate and come to dominate public discourse.

A brief sketch of Covid-19 denialism in three countries

In our study, we show Covid-19 denialism has been particularly noticeable in public discourses in the United States, Brazil and United Kingdom. Characterized by reluctance and delay, those societies bring similarities in the response to the pandemic by policymakers and the presence of significant opposition to public health measures designed to mitigate the spread of the virus. Partly due to this denialism, Covid-19’s impact on those three countries have been particularly pronounced. Of course, this is only one part of the story. Other analysis, such as from Kavanagh and Singh (2020), note the lack of state capacity in these countries that contributed to the inability to control the spread of the virus. As of January 2021, these three countries are still in the top five number of COVID-19 cases (along with India and Russia) and deaths along (Mexico), according with Worldometer.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro publicly disavowed all social-distancing and quarantine recommendations. Bolsonaro suggested that the pandemic was just a global hysteria and insistently perpetuated the myth that it only causes a gripezinha (little flu). Bolsonaro, like Trump, also publicly backed the use of hydroxychloroquine to treat symptoms, even without scientific proof of efficacy and safety. In April 2020, the Brazilian president also fired two health ministers in less than a month who advocated for social distancing and joined protests against a governor who has put economic activities in his state on pause. What little public health guidance that was given, focused on telling the public to “stay home and take care of yourself”, which individualized responsibility for Covid-19 without specifying collective actions taken to mitigate the pandemic’s risks. In 2021, facing an increasingly pressure to start mass vaccination nationwide, Bolsonaro publicly discourages people to get vaccinated and extensively shares unfounded concerns about potential Covid-19 vaccines-associated severe adverse reactions.

In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson initially opted for a “herd immunity” strategy before being confronted with catastrophic projections from an Imperial College research group, while facing high pressure from far-right groups to further ease social distancing guidelines. The primary rallying call for the public was centered on the National Health Services: “stay home, protect the NHS, save lives”. While this linked individual action to the desired outcome of protecting the capacity of medical institutions to save lives, the simple dictate to “stay home” provided an easy target for anti-lockdown protesters. In 2021, his attitude completely change since United Kingdom is now the European epicenter of new infections and had unfortunately spreading a new 30% mode deadly virus variant.

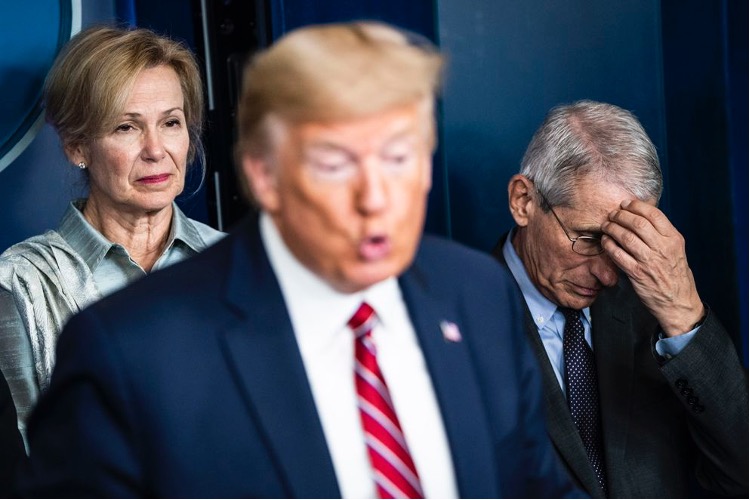

In the United States, former President Donald Trump repeatedly undermined his scientific advisors and tweeted out in support of anti-lockdown protests around the country in a bid to re-open the economy. Public health experts, working around Trump’s obstruction and sabotage, urged the public to stay home to help “flatten the curve”. This imaginary of flattening the curve focused solely on mitigation rather than containment and eradication. The statistical abstraction the pandemic also hindered the ability of the public to fully understand the human toll of the virus. Now, President Biden’s administration has to deal with the great challenge to create a vaccine distribution plan that can outpace the rapid spread of Covid-19.

Through our comparisons of these three countries, we hope to further trace the contours of Covid-19 denialism as a reaction to dominant pathogenic imaginaries and public expertise.

Working during the pandemic

About a year ago, after enjoying a 3-month visiting appointment at Columbia University’s Department of Sociology, invited by the professors Gil Eyal and Diane Vaughan, I left New York City a week before the pandemic was announced by WHO. Since then, me and Larry are working remotely and meeting periodically to discuss different parts of empirical research design, data collection and analysis.

Previous connections with each other were very important to make this work possible, since we have worked together on a comparative project that examines the trajectories of genomics and precision medicine in China and Brazil using a similar organizational process (Au and Silva, 2020). We are very proud of how STS is taking social sciences in account in the great global debates on the pandemic. Studying Covid-19 denialism is being a great opportunity to strength our community around a problem to be solved.

References

Au, Larry, and Renan Gonçalves Leonel da Silva. Forthcoming. “Globalizing the Scientific Bandwagon: Trajectories of Precision Medicine in China and Brazil.” Science, Technology & Human Values. 46 p. 016224392.

Eyal, Gil. 2019. The Crisis of Expertise. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity.

Hilgartner, S.; Miller, C., Hagendijk, R. (Eds.), Science and Democracy: Making Knowledge and Making Power in the Biosciences and Beyond, Routledge, London. 2015.

Jasanoff, Sheila. 2007. Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Jasanoff, Sheila et al. 2021. Comparative Covid Response: Crisis, Knowledge, Politics. Interim Report. 12 January 2021. Accessed 20 January 2021. Available at https://www.ingsa.org/covidtag/covid-19-commentary/jasanoff-schmidt/.

Kavanagh MM, Singh R. 2020. Democracy, Capacity, and Coercion in Pandemic Response: COVID-19 in Comparative Political Perspective. J Health Polit Policy Law 1; 45(6):997-1012.

Proctor, Robert. 2008. “Agnotology: A Missing Term to Describe the Cultural Production of Ignorance (and Its Study).” In Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, edited by Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, 1–33. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.