Having shown how the lab has evolved over the course of 15 years since its foundation, it is now time to reflect on where we are and where we are going.

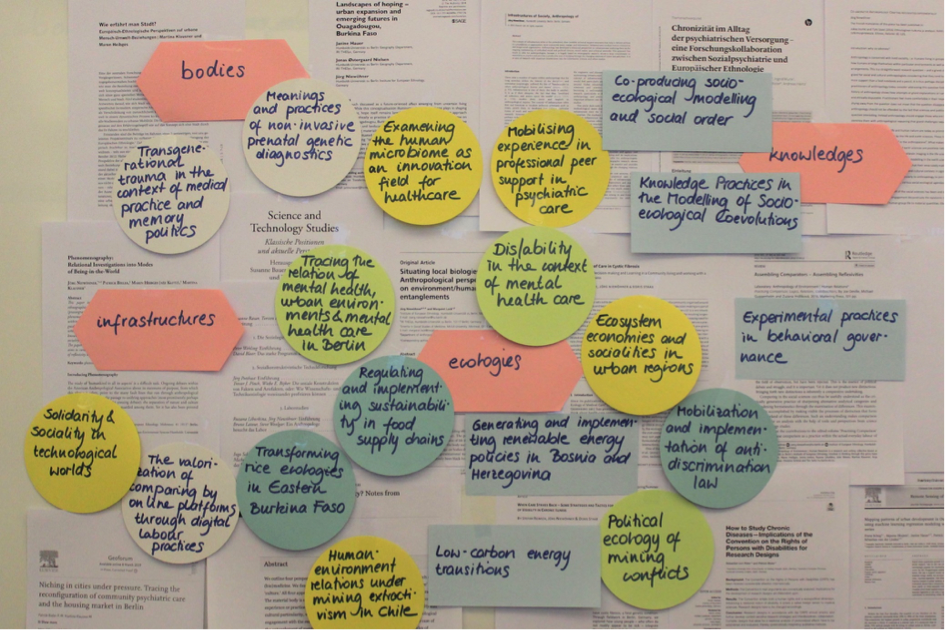

Our members’ research falls, broadly speaking, into two fields: life sciences, medicine, medical technologies and psychiatry on the one hand – and on the other sustainability, global land use, the role of modelling in human-environment systems and political ecology. Despite the broad range of topics we tackle in around 20 individual Master, PhD and Postdoc projects – ranging from the interconnections between (shifting knowledge about) medical care and urban environments, digitalization and memory politics1 and the subsequent changes in work systems/ecologies & governance2 to transformations of food and energy systems3 as well as resource socialities more broadly4 and finally, knowledge produced about such phenomena for example by socio-ecological modelling groups5 – and the geographical distribution of field-sites across Europe, the US, South America and West Africa we are committed to the idea of research as a collective endeavor. This is then our first point to make:

The Laboratory: Anthropology of Environment | Human Relations is more-than-project. Our self-understanding is more akin to what Ludwik Fleck has termed a thought collective:

“Although the thought collective consists of individuals, it is not simply the aggregate sum of them. […] A thought collective exists wherever two or more people are actually exchanging thoughts. He is a poor observer who does not notice that a stimulating conversation between two persons soon creates a condition in which each utters thoughts he would not have been able to produce either by himself or in different company. A special mood arises, which would not otherwise affect either partner of the conversation but almost always returns whenever these persons meet again.” (Fleck 1979 [1935], 41-44)

We are dedicated to providing and generating space in which ideas that are not quite finished yet, as well as research-in-the-making, can be openly discussed. Yet, our thought collective exceeds Fleck’s in that it is explicitly open for and actively seeking disconcertment. We seek to constantly oppose our own problematizations, approaches and findings, thereby seeking to expose their underlying assumptions and understandings to critique from within our collective as well as from the outside by welcoming guest researchers and discussing their works and comments to avoid becoming too comfortable. The lab is not a filter bubble.

Our commitment to work that is ‘more-than-project’ comes in different modes. Through constant reporting from our individual projects around our weekly meetings we establish contact points between projects, thereby fostering ideas, which exceed the individual members’ projects and can then be taken to broader discussions in STS, anthropology and the respective disciplines that define the fields we study, e. g. discussing the concept of niching through different fields in a joint paper (Bieler and Klausner 2019, see also below), working on the idea of situated modelling in a series of meetings together with the modelling6 community (Klein, Niewöhner, Unverzagt) or discussing the effects of situated politics of context for rice production systems in Uruguay and Burkina Faso for a workshop presentation (Hauer, Liburkina) to name just a few examples.

The framework of situated modelling stems from longer-standing discussions at the IRI THESys and will be elaborated on the basis of fieldwork currently under way in the field of participatory modelling (Unverzagt) and social-ecological modelling (Klein). Rather than striving for the single most accurate simplification of complex events, situated modelling acknowledges the contingency of simplifications and tries to turn this insight productive. As a research framework, situated modeling relates positive, predictive and quantitative approaches to reflexive, contextualising and qualitative approaches. It does so in ways that move beyond integration and critique.

Thinking across two initially unrelated PhD projects – on land-use and livelihood dynamics in the course of the introduction of large-scale rice production through a development project in Burkina Faso (Hauer) and the role of grand notions such as responsibility, economic growth and sustainable transformation in two distinct food supply chains (Liburkina) – allowed us to experiment with analytical prisms ranging from system to assemblage thinking and asking how de/stabilization is achieved and challenged in practice, while simultaneously raising questions about the construction and comparability of cases. The latter concern is taken up by the group as a whole in a couple of reading sessions on the case as well as on comparison.

Moreover, we cherish concept work on a more daily basis, making it less ‘quantifiable’ but not less productive. In our weekly sessions, we attempt to link conceptual discussions that emerge in one field to other fields as well as to overarching questions in STS and anthropology: comparison, juxtaposition, diffraction. For example, we’ve traced the parallels in the uses of the concepts of hope and experience in the anthropological records in order to circumvent the fallacy of adding another definition of the concepts instead of focusing on the work these concepts do in the world and their effects. Although, these discussions did not result in joint outputs, they enriched the research they accompanied (Hauer, Nielsen, and Niewöhner 2018, Schmid 2019). Paralleling our attempts to think through rather than within projects, we have ongoing discussions about how to empirically trace and conceptually frame relatedness, a question that connects many of our ongoing projects, whether they deal with supply chains, mental health care in urban space or the emerging rice market in Burkina Faso. Exchanging concepts from different fields, switching lenses and thought traditions and exploring what they might add to our own thinking is an inspiring exercise that helps us to strengthen our arguments and positions.

This brings us to our second point: what holds the lab together is more-than-discipline. STS has been, right from the start, an inter-disciplinary endeavor. Bringing it into an established discipline such as Social and Cultural Anthropology and European Ethnology, the challenge has been to make an argument for what our approach has to offer to that discipline. Today, lab members are no longer an exclusive group of anthropologists with an interest in STS thinking, rather the lab has assembled as well as produced researchers that transcend disciplinary boundaries coming from or working in anthropology, geography, sociology, medicine etc. We all share an interest in discussions beyond disciplinary boundaries. Yet we are all also eager to take these discussions back to the centers of their respective disciplinary discourses in order to foster friction rather than new comfort zones. By doing so, we are committed to upholding the critical potential we believe STS has so productively developed.

Accordingly, the Lab strongly believes in the importance of long-term co-laborative ethnographic projects carried out in research teams, taking initiatives such as the Matsutake Worlds Research Group or The Asthma Files as examples. So far, this has proved especially productive in the field of social psychiatry. Steady exchange between the projects has led us to a detailed exploration of the ecologies of psychiatric expertise. Starting with fieldwork on different psychiatric wards, our inquiry into the classification and phenomenon of chronicity reached out to the everyday of public community mental health care services, their public administration, and the lives people lived once released from inpatient care. Examining the links between mental distress and (the transformation of) urban environments beyond the psy complex, resulted in recent research on and with administrative agencies, political institutions and lobbying groups. Ongoing discussions with anthropologists, sociologists, psychiatrists, and geographers from Germany, the UK, and Switzerland, reinforced our approach of investigating the situated experiences of people with psychiatric diagnosis as socio-material practices co-constituted by and co-constitutive of knowledges, bodies/minds and (urban) environments. (Klausner 2015, Bister, Klausner, and Niewöhner 2016, Bister 2018, Bieler and Klausner 2019)

The lab pushes ethnographic inquiry and theorizing to be more-than-deconstruction. All lab researchers share the belief that our research needs to amount to more than critically deconstructing any sort of phenomenon or prevalent problematizations on and of the fields we research. We, therefore, aim at co-laborative and response-able research designs and at keeping the possibility open for situated interventions, feedback loops and generative critique. In two medical technology development projects, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, for instance, we contrasted individualized approaches of compliance and technology use with our empirical analyses of daily health care practices and modes of living and working with medical devices. By doing so in regular project meetings together with partners from engineering and through a continuous ethnographic presence, we created space for irritating basic assumptions that were to be black-boxed in the technology under development (Klausner 2018). We do not wish to overemphasize our impact on the way in which the projects developed nor on the general technical set-up of the technologies. Nevertheless, we insist that ethnographic co-laboration and intervention adds a dimension to established research on the ethical, legal and social aspects of technology development as well as user-centered design and design thinking (Seitz 2017).

Although our fields as well as modes of research differ considerably in how they allow for different degrees of co-laboration, we share a commitment to ethnographic research and theorizing not only of but also in, with and for the world as the ultimate vantage point.

So, as you can tell from this text, we are not only more-than-human, but super-human, really: critical and generative, engaged and reflexive, versed in disciplines but also transcending them. Above all, of course, we are more-than-serious, so get in touch and join our sessions if you are ever in Berlin or would like to visit us.

1 Current research projects in this area deal transgenerational trauma in the context of medical practice and memory politics, professional peer support in psychiatric care, anti-discrimination law, dis/ability in the context of mental healthcare and palliative care, relations of mental distress, urban environments, healthcare infrastructures, and public administration, and non-invasive prenatal genetic diagnostics.

2 These projects are about the valorization of comparing by online platforms, emerging high-technologically driven economics and socialities, solidarity and sociality in a technological world, the human microbiome, and experimental practices in behavioural governance.

3 Examples are projects on renewable energy policies in Bosnia and Herzegovina, low-carbon energy transitions, rice ecologies in Burkina Faso, and food supply chains of bulk consumers.

4 Such as projects on the political ecology of mining conflicts and mining extractivism.

5 See the projects on modelling complex systems in the environmental sciences and the co-production of socio-ecological modelling and social order.

6 The models we are concerned with are numerical models, computer simulations based on mathematical models. For now we are interested in models that take socio-ecological phenomena as their object (on various scales and with different symmetries).

Literature

Bieler, Patrick, and Martina Klausner. 2019. “Niching in cities under pressure. Tracing the reconfiguration of community psychiatric care and the housing market in Berlin.” Geoforum. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.01.018.

Bister, Milena D. 2018. “The Concept of Chronicity in Action: Everyday Classification Practices and the Shaping of Mental Health Care.” Sociology of Health and Illness 40 (1):38-52. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12623.

Bister, Milena D., Martina Klausner, and Jörg Niewöhner. 2016. “The Cosmopolitics of ‘Niching’. Rendering the City Habitable along Infrastructures of Mental Health Care.” In Urban Cosmopolitics. Agencements, Assemblies, Atmospheres, edited by Anders Blok and Ignacio Farias, 187-205. London, New York: Routledge.

Fleck, Ludwik. 1979 [1935]. Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. (First published in German, 1935) ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hauer, Janine, Jonas Østergaard Nielsen, and Jörg Niewöhner. 2018. “Landscapes of Hoping – Urban Expansion and Emerging Futures in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.” Anthropological Theory 18 (1):59-80. doi: 10.1177/1463499617747176.

Klausner, Martina. 2015. Choreografien Psychiatrischer Praxis: Eine Ethnografische Studie zum Alltag in der Psychiatrie. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Niewöhner, Jörg. 2016. “Co-laborative Anthropology. Crafting Reflexivities Experimentally.” In Etnologinen tulkinta ja analyysi. Kohti avoimempaa tutkimusprosessia, edited by Jukka Joukhi and Tytti Steel, 81-125. Tallinn: Ethnos.

Niewöhner, Jörg, and Margaret Lock. 2018. “Situating local biologies: Anthropological perspectives on environment/human entanglements.” BioSocieties. doi: 10.1057/s41292-017-0089-5.

Schmid, Christine. 2019. „Ver-rückte Expertisen: Eine Ethnografie über Genesungsbegleitung. Über Erfahrung, Expertise und Praktiken des Reflektierens im (teil )stationären psychiatrischen Kontext. Doctoral Thesis, handed to the Institute of European Ethnology at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin on February 19th, 2019.”

Seitz, Tim (2017): Design Thinking und der neue Geist des Kapitalismus. Soziologische Betrachtungen einer Innovationskultur. Bielefeld: Transcipt Verlag.