“Let’s pause for a while, follow a procedure and search for different sensors that could allow us to recalibrate our detectors, our instruments, to feel anew where we are and where we might wish to go.

No guarantee, of course: this is an experiment, a thought experiment, a Gedankenausstellung.”

(Field book, p. 1)

That voice is familiar. It appears in many texts and lectures, navigating between directly calling on the reader – never without a sense of humour, but seriously upset about the way we continue to act out modernity – and considerately trying out new ideas and forms of de-modernisation. In short: “r-M!”

“Gedankenausstellung” is one of these ideas, coined by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, who since their “Making Things Public” (2005), have tried to open up new ways of relating to the world through the mode of the discursive exhibition. In “reset Modernity!” it signals the theoretical work to be done by the visitors once they have gone through the six “procedures” that structure the exhibition. The “field book” is another:

“As the name ‘field book’ indicates, you are invited to do a bit of research yourself.”

(Field book, p. 2).

As an impatient visitor of exhibitions, but an anthropologist passionate about analysing knowledge in the mode of the exhibition, I was most curious about the making of “reset Modernity!” when I visited it on its opening weekend. Would space be reserved for reflection on how this Gedankenausstellung became an Ausstellung? And if so, what kind of spatial arrangement could express the localising qualities of this very representational work?

As it turns out, there was. Firstly in the catalogue, which was too heavy to carry, and will be a source for future reading. Here, a seventh procedure with the title “In search of a diplomatic middle ground” had been added. The chapter provides a visual and textual documentation of the conferences, workshops, symposia and plays that took place in the context of AIME — the ERC-funded research project and network based in Sciences Po’s médialab in Paris. The website, which has been developed as a working tool for the group, contains additional materials, including interviews with Bruno Latour on the question, “What is a Gedankenausstellung?” (http://modesofexistence.org/what-is-a-gedankenausstellung/). When it comes to learning about the making-of process, the photographs of their work sessions are potential sources of information – they show people sitting around tables covered with document folders, bottles of soft drinks and plates of sweets, discussing plans that have been projected on the wall. It features photographs and an audio-visual recording of the curators visiting the ZKM in 2015, bent over plans and examining the future exhibition space. It also shows the “statement of intent”, which prompted the following comment: “It sounds exciting. Stay strong and hold on to your original vision. Alicia Flynn (a year ago)” (http://modesofexistence.org/statement-of-intent-for-the-aime-exhibition-at-zkm-2016/)

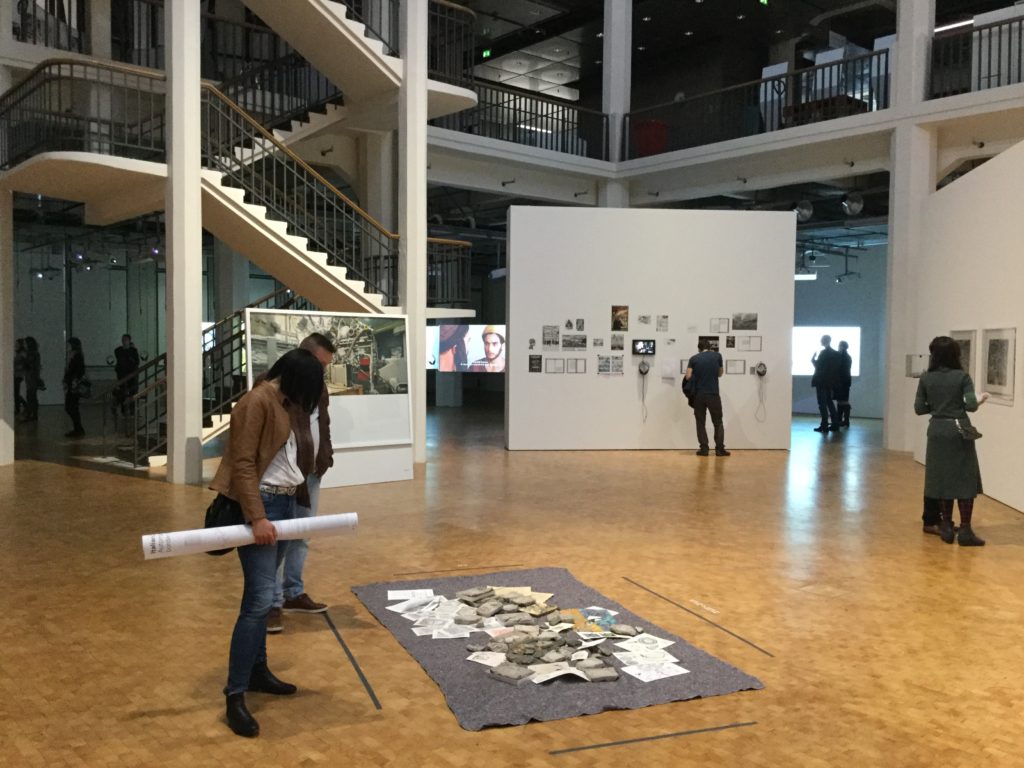

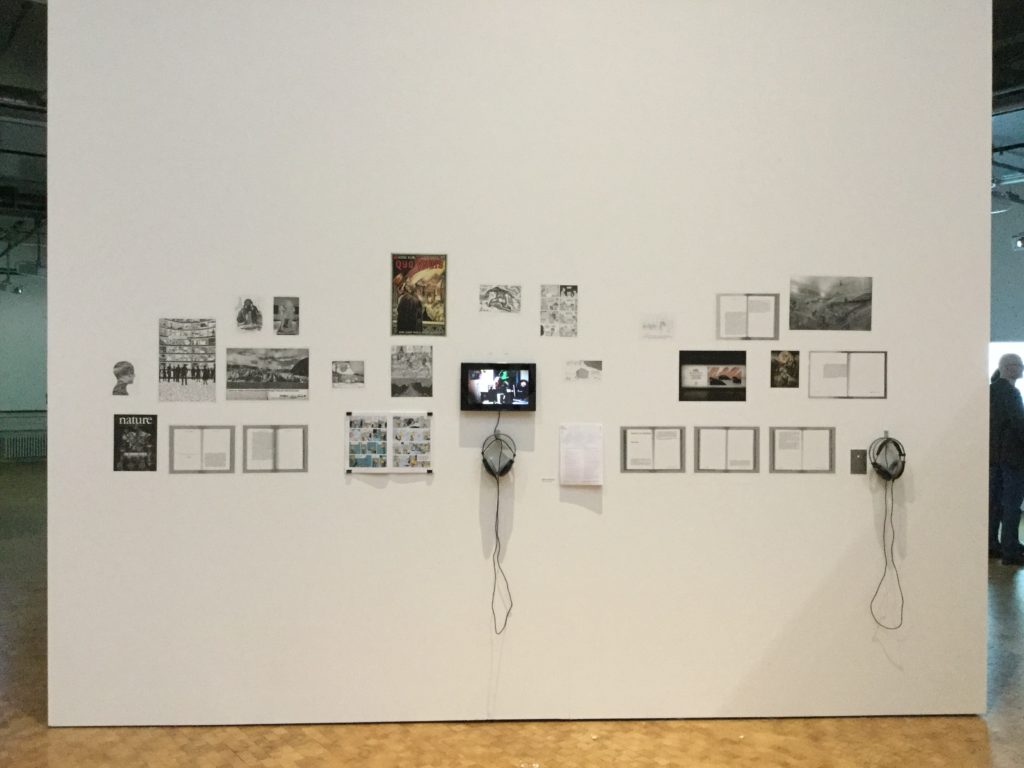

Did they stay strong? And was that the right approach? (It shouldn’t be, see Latour/Weibel 2007: pp. 94-95) They did keep to their plan, and while the catalogue and website document how the research network took on the risks of interdisciplinary work (intertwining research, debate and theatre with analogue and digital design in different locations and constellations) the exhibition includes traces of their original working practice in the form of “stations” implemented in each procedure. Here, thematically related quotes, notes, images and audio-recordings are provided and loosely arranged on a single white wall. These arrangements are aesthetically reminiscent of the associative Warburgian atlas production – without claiming to be exhaustive.

Quite the opposite: These stations point directly to another, virtual actor — potentially a zettelkasten of the AIME team and its collaborators, which could be a probable source for the arrangements. The looseness of the wall arrangements and the virtual zettelkasten cautiously suggest the existence of selection, but not to the ways in which the selection took place. Which lines were drawn between those artworks and references that became part of the spatially, temporally, financially limited exhibition-project? Which artworks and references made their way into the exhibition while transgressing these lines? And which ones never did become a part of it, despite having the strongest of qualifications1 Since much of the “field book” isn’t a “fieldwork notebook”2, the stations don’t offer these types of insights into the representational work. Given that these processes are always driven by tension and passion – which shape the agency distributed between the actors – these walls have a lightness, they breathe and invite the visitor to do the same.

But do they provide the quiet that, as Bruno Latour mentioned in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist (http://modesofexistence.org/what-is-a-gedankenausstellung/, 26:14), is necessary for a reset? The field book proclaims that they are “a sort of workplace … this is where you will find more information and where you can discuss the path of the inquiry” (field book, p. 2). Here something might have been lost between the original vision and its spatialisation.

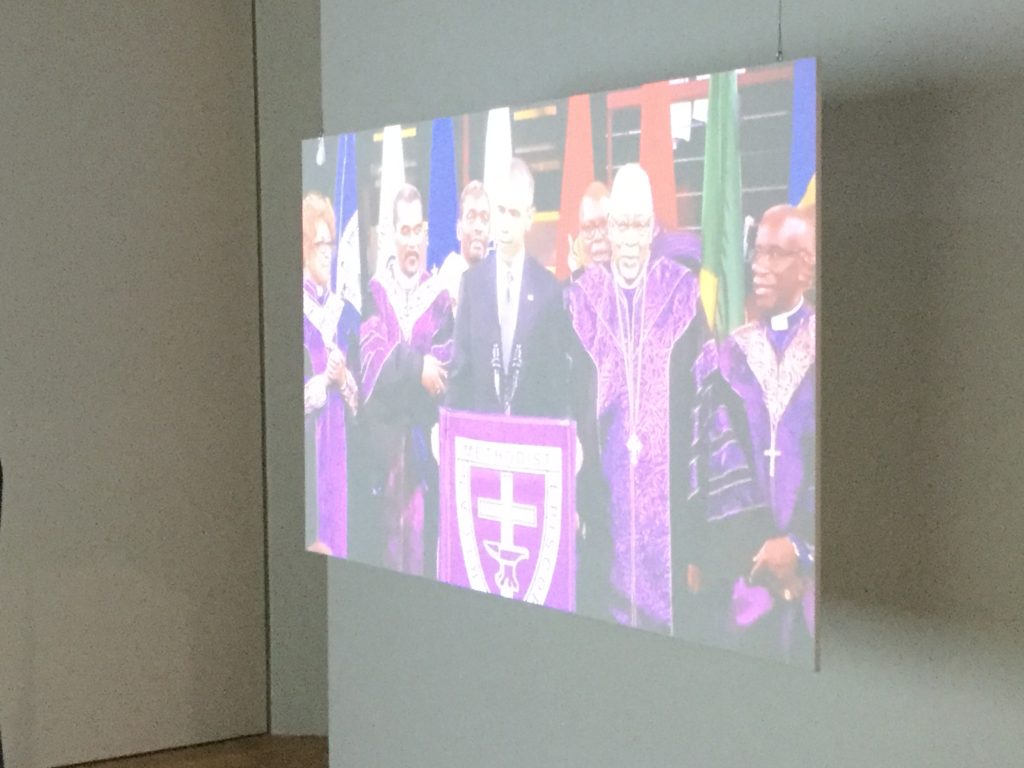

The very discreteness of this AIME-archive (the table with books at the intersection of three procedures should also be mentioned) is partially the result of the large, all-consuming two-dimensional artworks that surround these stations. Walking through the exhibition, these spectacular images again and again captured my attention: the more-than-realistic, staged photographs of Jeff Wall showing scientific practices; Armin Linke’s photographic work, which seemed to be part of almost every procedure, and simultaneously points to humanity’s intriguing megalomania and smallness and, visible from far away, at the end of the first exhibition hall, the floating walls of film projections in procedure five. The latter, called “Secular at Last”, resonated with the large scale of the other pictures. One work in this procedure is spatially secluded by a triangular installation of screens: “Obama’s Grace” (Lorenza Mondada et al, 2016). Here, the performative force of Barak Obama’s combination of political statement and religious “sound” is disturbingly intensified. An analytical transcript on one of the screens, however, demonstrates the extent to which this intensity stems from both the president and his parish. When standing between these three screens, the need for a way out of modernity’s binding forces could not be more obvious. Time for a Gedankensprung!