“[W]ays of studying and representing things have world-making effects” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017: 30). With these words Sara Bea, postdoctoral researcher at University of Linköping, opens her talk on normativities in STS research and storytelling during the EASST2018 Conference. She acknowledges that practices such as observing and representing are ways of intervening and constructing (Hacking, 1983). Researchers constantly make choices: which case to select, who to talk to, what to include or exclude, how to tell stories. They have to decide which ethics they want to enact. Bea proposes that STS researchers should move beyond announcing the bad and promoting the good. She calls for sharpening STS tools and vocabulary to grasp the complex entanglements of good and bad, and to tell alternative stories, which expand the interstitial.

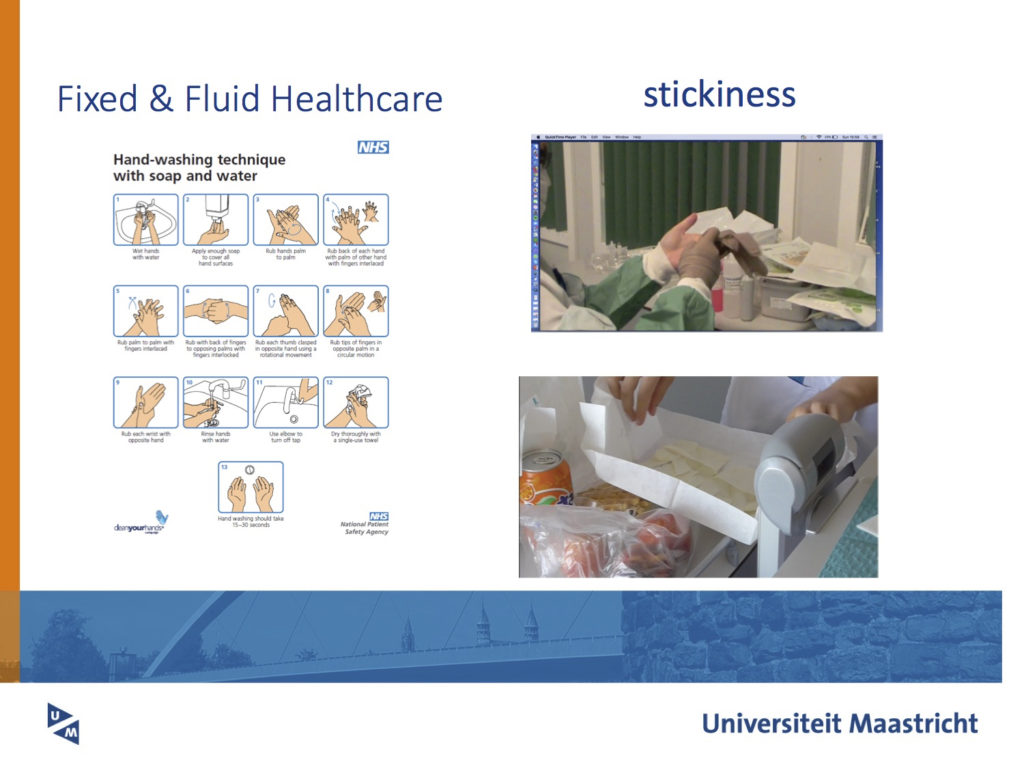

Jessica Mesman, associate professor at University Maastricht, and Su-Yin Hor, lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, follow this call in their presentation on “Sticky business” in which they introduce the notion of “stickiness” to analyze and intervene in interstitial spaces in health care. Stickiness is in-between fixed and fluid practices; it is sticky between supposedly stiff and preservable practices on the one hand, and those that seem to be open, flexible, and easy to adjust on the other. Stickiness occurs in health care, for instance, when clinicians make efforts to follow protocols, but are confronted with the hectic and surprises of everyday work, such as an unexpected admission of two patients at the same time or an emergency call (Figure 1). Tension between fixed and fluid produces sticky practices that are stiff enough to be directive and pliable enough to be adjustable to constantly changing work contexts. This tension is productive because it allows for practice improvement. For example, Mesman (Mol and Mesman, 1996) observed how a nurse introduced a drip system for stomach-tube feeding at a neonatal care ward. The nurse intended to optimize the feeding protocol so that she did not have to hold a bag containing food above a baby for a long time with a trembling arm and lots of other things to be done.

Mesman, Su-Yin Hor, and Bea regard the space between two extremes – between fixed and fluid, good and bad – as a locus of potential for intervention, either by telling stories that unsettle the polarity of good and bad or by improving practices. When listening to their talks, Helen Verran’s captivating book Science and an African Logic came to my mind. Verran describes “disconcertment” as a fairly common but often overlooked “fleeting experience” (2001: 5) when doing research. It occurred to her when she encountered interruptions that did not fit her line of argument during fieldwork, working as a primary school teacher in Nigeria. According to Verran, being attentive to disconcerting experiences enables a researcher to detect productive tensions at actual times and places. Rendering these tensions and actors’ creative practices explicit offers “the possibility of innovation, a way that things might be done differently to effect futures different from pasts” (20). Verran’s concept of disconcertment seems to provide an alternative vocabulary to the notion of stickiness. Whereas sticky moments allow to navigate between fixed and fluid practices, disconcertment protects a researcher from becoming trapped in the foundationalist tendencies of universalism and relativism. By cultivating attention for disconcertment, Verran moves away from her initial conclusion that math is culturally relative, that an incommensurability separates ‘Western’ and ‘other’ knowledges, and that children should be taught either one or the other. She acknowledges how Nigerian teachers navigate between and merge Western and Nigerian maths, how they engage in “sticky business” to resolve tensions.

I approached Mesman after her presentation to ask how stickiness relates to Verran’s concept of disconcertment. Mesman appreciated my comment as an incentive to scrutinize how stickiness overlaps with disconcertment and what it enables researchers to see and do that disconcertment does not. Stimulated by Bea’s call for sharpening vocabulary and tools to capture normativities in STS research, I reflected upon what stickiness could do for my own research. My ethnographic fieldwork in a European biomedical research institute where neuroscientists study the impact of Buddhist meditation on healthy aging has been influenced by Verran’s work. I have been watching out for neuroscientists’ creative and innovative practices for dealing with diverse kinds of tensions: How do scientists comply with ethical standards while struggling with the bureaucratic burden that grows with increased regulation? How do supervisors take responsibility for acquiring ethical approval of research projects that they co-conduct with their PhD students without interfering with a student’s learning process? How do researchers deal with their uneasiness when they show videos of disabled individuals or scenes filmed in Third World countries to research participants to capture how these participants emotionally react to people’s suffering? Observing how these videos were displayed in the context of a meditation research project left me with a feeling of disconcertment. I had the impression that these videos perpetuated negative stereotypes about minorities and foreign countries. However, Verran’s book does not provide guidance for what to do with my disconcertment besides including it in my fieldnotes and eventually in my dissertation.

As Verran developed her conceptual tools only after returning from her fieldwork to Australia, she merely enacts ethics in storytelling by foregrounding what tends to get “excluded, marginalized, forgotten, unconsidered, or disfigured in the process of normalizing social and political action” (Schillmeier, 2011: 514). Yet, I was wondering how I could use my feeling of disconcertment as a tool to actively engage the setting that I am studying to find out how I could bring value to those who I am studying (cf. Downey and Zuiderent-Jerak, 2017: 225). For this purpose, the notion of stickiness seems to be useful. As an ethnographer at a ward, Mesman enacts ethics both in writing and at her field site. When writing about sticky moments and actors’ productivity in adjusting practices, she increases their and others’ awareness of resources available for resilience (Mesman, 2007). At the ward, Mesman uses video-reflexive ethnography (VRE) as a method to capture sticky moments in daily routine on film. Discussing the video footage with health care practitioners, Mesman intervenes by stimulating reflections on how to adjust fixed protocols and cultivate creative practices. She actively contributes to practice optimization, for VRE requires practitioners to sit down and reflect on their practice for a while. Inspired by Mesman and Su-Yin Hor’s “Sticky business”, I will try to decelerate the pace of laboratory routine by asking neuroscientists to sit down with me on a regular basis. I will bring moments in which I have felt disconcerted up for discussion and ask scientists to answer questions that probe for ethical and societal dimensions of their research (cf. Fisher, 2007). Initiating sticky conversations, I enact ethics by adding some syrup to laboratory life so as to make it a little more sweet, tasty, and hopefully better.

The pictures juxtapose a fixed hygiene protocol and the fluidity of actual hygiene practices in moments of emergency that leave no time to properly clean up the work space.

References

Downey G L and Zuiderent-Jerak T (2017) Making and Doing: Engagement and Reflexive Learning in STS. In: Felt U, Fouché R, Miller C A and Smith-Doerr L (eds) The Handbook of Science and Techology Studies. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Fisher E (2007) Ethnographic Invention: Probing the Capacity of the Laboratory Decisions. NanoEthics 1: 155-165.

Hacking I (1983) Representing and Intervening: Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mesman J (2007) Disturbing Observations as a Basis for Collaborative Research. Science as Culture 16(3): 281-295.

Mol A and Mesman J (1996) Neonatal Food and the Politics of Theory: Some Questions of Method. Social Studies of Science 26: 419-444.

Puig de la Bellacasa M (2017) Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Schillmeier M (2011) Unbotting Normalcy: On Cosmopolitical Events. The Sociological Review 59: 514-534.

Verran H (2001) Science and an African logic. Chicago: Chicago University Press.