In October 2017, the conference ‘Building Care: Intersections of Health and Architecture’ took place at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. The symposium brought together scientists, policy makers, architects and even some patients to talk about how places of care and place-making for care matter. The participants tried to connect and exchange on place as a unit of analysis in thinking about healthcare. Their different ideas about place-making (building-making for architects; people and budget centered for policy makers, and a process of meaning-making for the STS scholars) made for rich interdisciplinary discussions on how to think about and do place.

STS and Place

The idea to organize a conference explicitly dealing with places and the making of places originated in what the organizers felt was an incomplete conceptualization of place in STS. Certainly, the underlying importance of place has been there from the beginning, as knowledge production was tied to a particular site: the laboratory. From then on, STS has tended to categorize knowledge, based on the places where it happens (Henke 2000). Tom Gieryn made this relationship explicit when he distinguished between lab and field knowledge (2006) and tied knowledge production to particular truth-spots (2002). There has been STS work done on the importance of particular places as political and techno-cultural assemblages (e.g. Marres 2013 on eco show homes or Farias & Wilkie 2016 on studios), but the relationship between place-making and care has not been explicitly theorized.

How to challenge ourselves in thinking further about place? Looking beyond STS seemed like a good way to start exploring. The conference was conceived as an interdisciplinary, open conversation with policy makers, cultural geographers, historians and, importantly, the experts on place-making: architects.

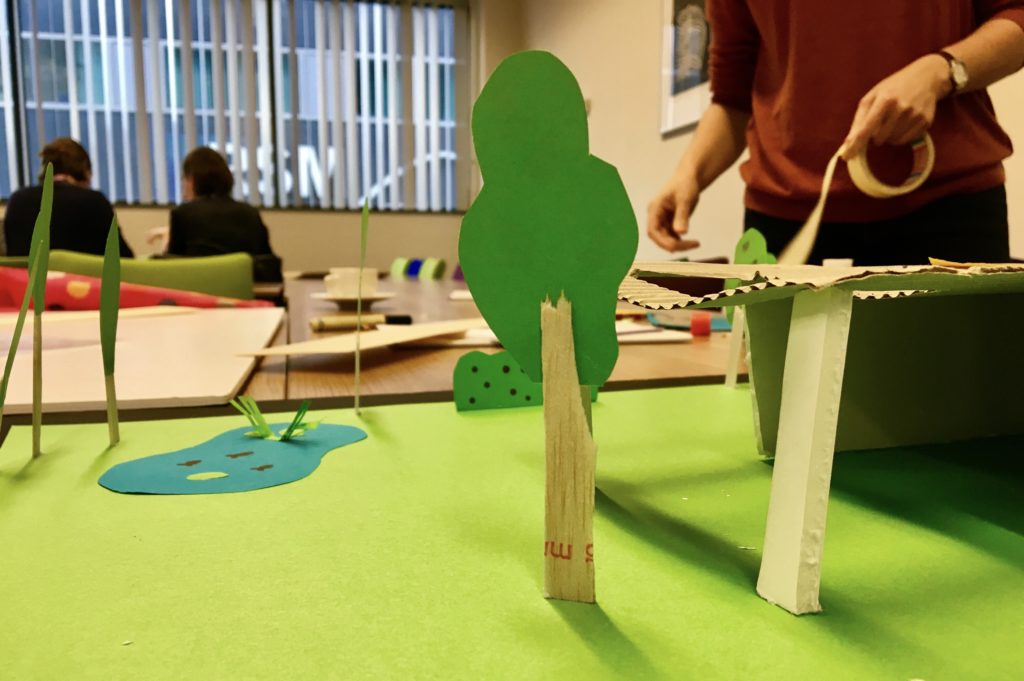

Courtesy of the author.

Places: transient and concrete

The morning session was structured around three keynotes and showcased very different approaches to place. Tim Cresswell, a human geographer, broke down place into three ingredients: location, locale and sense of place and, quoting Tuan, referred to place as “a field of care”. He then outlined a theory of place, consisting of the overlapping spheres Materialities, Meanings and Practices, which are intersected by vertical and horizontal axes of temporality. This conceptualization becomes more intricate and is too complex to summarize here, but it is important to note that for Cresswell places are not bounded entities. Rather, places are intersections of numerous forces coming together and linking in nodes of relations that are always articulated in particular temporalities. In this understanding of places, they are emergent centers of meaning, transient and unbound.

The architect AnneMarie Eijkelenboom’s keynote was conceived with a very different concern: how are places of care built and what can this process teach us about place-making in healthcare? Her talk focused on the way built environments affect health and perception. Place was a concrete object in this keynote – it was a building, a garden, a room. Yet, it was also a process of continuous considerations of different materials, physical elements and users. In this talk places were broken down to numerous ingredients and the three overlapping spheres – Materialities, Meanings and Practices – were made visible in the examples of care buildings that AnneMarie discussed.

Designing Death and Dying

The afternoon parallel workshop sessions encouraged participants to think through the different conceptualizations of place, presented in the keynotes. Hands-on cases were the hospice as a place for dying and Maggie’s cancer centers as places of (physical and emotional) comfort. Ken Worpole, who had delivered a keynote in the morning on the history of hospices in the U.K., discussed how sense of place frames the experience of dying. The design and build of hospitals is geared toward cure. The materialities, practices and meanings of hospitals converge to fight for the preservation of life, often resulting in prolonged suffering for both patient and loved ones. CPR procedures have become so thoroughly embedded in western healthcare practices that it is now routine response to most deaths. The particular environment of hospices is, on the other hand, geared toward care: a dignified way of dying. This insight made an impression on the architects in the room, who started thinking about the ingredients necessary to create the intimacy and calm of places for death, but within hospitals. It is a good question to ask about place-making, as well. Does place-making consist of ingredients that can be pinned down? How can a place’s transient quality be captured and scaled up or down? Place-making for care is very different from place-making for cure. Materialities must align with practices and meanings; otherwise places ‘don’t work’.

Place-making is doing [together]

In one of the afternoon sessions participants were challenged to build places of care in small groups. The groups were purposefully diverse, including architects, doctors, academics, policy makers and patients. Each group was given modeling foam and basic supplies to make a place by focusing on a care process. The idea behind the workshop was to do place, as opposed to talking about place. Each group had differing and sometimes divergent concerns, but these had to be articulated in very practical terms. The question ‘what is a healing environment’ was understood and answered in different ways. In the plenary discussions that followed, it became clear that place-making is about working with multiplicities, which sometimes fit together and sometimes fall apart. The doing of places – the correct lighting, sound isolation, view toward a garden, privacy, the feeling of comfort, the feeling of home – is even more complex in terms of healthcare. Places of care must be safe, for both patients and professionals, yet they must also be cozy. They must be a physical articulation of a balance between care and cure, between patient autonomy and professionals’ ability to perform their tasks. Beyond materiality, places are also “fields of care” and meaning making, but also of politics and policy. Places are made of people, objects and ideas, couched in particular temporalities. They are planned, designed and built, but are in fact contingent and emerging assemblages.

Place Agenda

The conference was an attempt to set a place agenda in healthcare and STS. Borrowing insights from human geography, we know that places are not empty containers that may be filled with the importance of people and practices, but that they are co-produced with people and practices, while producing meaning within particular temporalities. Furthermore, we may say that places are always there, acting as a backdrop, while linking practices and objects in nodes of relations.

What does such an insight offer healthcare studies? A place-centered analysis may be particularly useful for understanding governance arrangements and practices. Oldenhof et al. (2016) argue that the governance of healthcare is being done through particular spatial arrangements, which are often viewed as a neutral backdrop to policy making, but must be taken seriously as governance tools. At the intersection of architecture, design and health, place may play an important role in interrogating popular notions, such as evidence-based design (EBD) and healing environments. In STS, work on places as sites of knowledge production and even political ontology has shown that places have the capacity to unpack social complexities (cf Yaneva 2012). Using place as a productive analytic lens will mean developing the relationships between place and knowledge further and tracing the ways places are productive in multiple ways.

This ‘place agenda’, as the conference participants referred to it, is more of a tentative mapping of the issues and methodologies that may benefit from a place analytical angle, and certainly not a thorough program. Conceiving of places as “fields of care” in multiple may open up spaces for thinking further on governance, politics, ontology and the meaning of care.

The conference Building Care was organized by the Erasmus School of Health Policy and Management (ESHPM) with the support of the Netherlands Graduate Research School of Science, Technology and Modern Culture (WTMC).

Bibliography

Farías, I & A. Wilkie (2016) Studio Studies: Operations, Topologies and Displacements (Routledge: New York)

Gieryn, T.F. (2002) ‘Three Truth-spots, Journal of History of the Behavioral Sciences’ 38 (2): 113-132

(2006) City as Truth-spot: Laboratories and Field-Sites in Urban Studies’, Social Studies of Science, 36 (1): 5-38

Henke, C.R. (2000) ‘Making a place for science: The field trial’, Social Studies of Science, 30 (4): 483–511

Marres, N. (2013) ‘Why political ontology must be experimentalized: On eco-show homes as devices of participation’, Social Studies of Science, 43(3): 417-443

Oldenhof, L., Postma, J. & R. Bal (2015) ‘Re-placing Care: governing healthcare through spatial arrangements’ in Ferlie, E., Montgomery K. & Reff Pederson A. (eds), Oxford Handbook of Healthcare Management (Ofxord: Oxford University Press)

Yaneva, A. (2012) Mapping Controversies in Architecture. (London: Ashgate)

MerkenMerken

MerkenMerken