1. Introduction. What is solidarity?

In their daily routine, healthcare workers engage with their patients in various ways, ranging from attentiveness and kindness to inattentiveness or even (un)conscious discrimination. In this article, we analyse healthcare workers’ enactment of solidaristic practices to support disadvantaged groups. On the basis of observational data from interactions of refugees with the healthcare system and qualitative interviews in Vienna, Austria, we suggest that healthcare workers play an important role closing structural gaps within a solidarity-based healthcare system. Drawing attention to these often unnoticed solidaristic practices means to acknowledge forms of what we call lived solidarity.

Solidarity as Practice

During the Covid-19 crisis, solidarity has been a widespread, and maybe overused, term. From global cooperation in vaccine development to neighbours running errands for each other, a wide range of practices have been celebrated as solidarity. The longer the crisis lasts, however, the clearer it becomes that people are not only moving closer together, but that the fault lines between people are becoming more pronounced as well (see Prainsack, 2020). Also for this reason, it is important to define what we mean by solidarity before delving into our empirical analysis.

Building on the solidarity literature, particularly in the English-speaking world, we see solidarity primarily as practice: and specifically, as practice that expresses the willingness of people to support others with whom they see themselves as having something in common in a relevant respect (Prainsack & Buyx, 2011: 2017). In each case, the specific practice provides the reference point for what is and can be recognised as relevant commonality: For example, if someone sees a call to donate blood, or even a kidney, that person’s willingness to respond to that call will often be influenced by whether they have a personal connection to the issue at hand. If the person has a family member or friend whose life was saved by a blood, or organ donation, then they will often be more willing to respond to the call than if they have no connection to the topic at all.

Moreover, we always practice solidarity in specific situations and contexts. As women, we are not automatically in solidarity with all other women. When we support a woman who has become the target of sexist harassment or discrimination, for example, we may do so because we ourselves have experienced such harassment, or because our friends or family members have. (And one does not have to be a woman to be solidaristic with women who become the target of such discrimination). But we might not be solidaristic with this same woman if she asks us for support in a political campaign that does not correspond to our views. The concrete context of action indicates, in each individual instance, what commonalities or differences give rise to solidaristic action: No one is solidaristic with others in an abstract sense.

When we observe discrimination and are bothered by it to the extent that we take action against it, we exercise solidarity with those suffering discrimination in a specific instance or context, despite all the other differences that exist between us: the people we support may have different political goals, religious or spiritual beliefs or lifestyles. Solidarity, thus, does not mean ignoring differences and pretending that they do not exist: rather, it means that despite the differences that exist between people, letting the similarities and commonalities become the source of our actions – especially when these similarities or commonalities are not “obvious”.

As Prainsack and Buyx have emphasised in their work (e.g. Prainsack & Buyx, 2017), that the “recognition” of similarities or commonalities in a relevant respect, which is the basis for solidaristic action to emerge, is not, however, a mere determination of “objectively” existing commonalities, which may be essentialist or even nativist. To a large extent, the differences and similarities that we see ourselves as having with others are things we have learned to see. A person who grew up in a family and society that placed emphasis on every person being equal, irrespective of their skin colour, gender, and beliefs, will find it easier to see commonalities amidst all other differences than a person who grew up learning to think of everyone who did not have the same religion, ethnicity, or political views as “different”. Public and political discourses that play out in different groups of the population against each other can have a big impact on the thinking and perceptions of people in this respect.

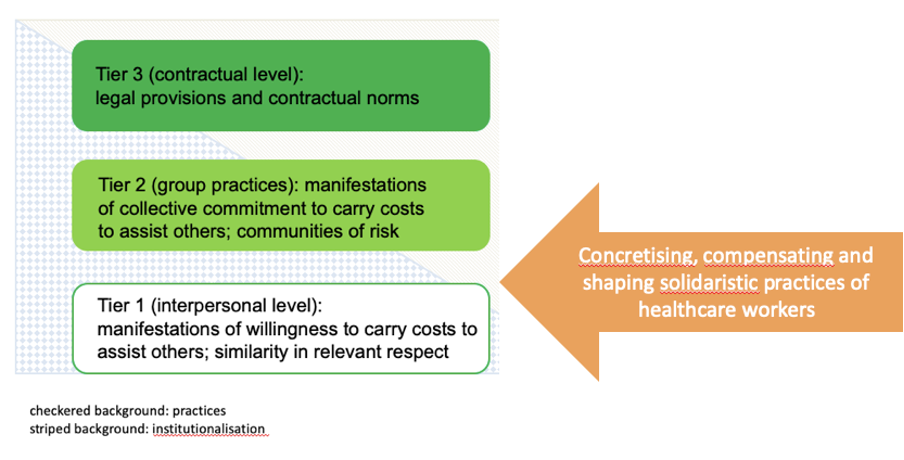

We have already given a few examples of the forms that solidaristic practice can take at the interpersonal level: A person recognises a part of herself in another person (or persons) and does something to support that other person(s), even if it incurs “costs” for her (this cost need not be financial, but it can also be time, comfort, or physical well-being – as is the case with the example of blood or organ donation). Building upon Prainsack and Buyx’ work (2011, 2017), we refer to this interpersonal, person-to-person solidarity, which is primarily about the concrete practices of individuals, as ‘tier 1’ solidarity. But of course, solidarity can also take other forms; for example, when it becomes so “normal” within a collective – a group, a community, an association – that it becomes a shared, expected practice (‘tier 2’). When solidaristic practice expresses itself in administrative, bureaucratic, or other norms, then we speak of ‘tier 3’ solidarity. A progressive tax system is an example for this latter, “hardest” form of solidarity, or a solidarity-based healthcare system into which people pay not in proportion to the costs they will incur according to actuarial calculations, but according to their financial means. And from which each person receives not only the services they can or could pay for, but those they need.

These different levels of solidarity are not only helpful in distinguishing “softer” (fragile, frequently changing) from “harder” (more stable, legally enshrined) forms of solidarity, depending on how quickly and easily they can change. The distinction between the three levels also offers the possibility of a more precise analysis of different forms and institutions of solidarity, rather than simply saying that solidarity is increasing or decreasing in a society. For example, during the Covid-19 crisis, some countries had large fluctuations in the intensity and prevalence of person-to-person (tier 1) solidarity, but continuously increasing support for solidaristic institutions such as publicly funded public health programs and institutions, well-equipped and publicly funded or solidarity-based healthcare systems, and even social housing (tier 3) (e.g. Lievevrouw & Van Hoyweghen, 2021).

In the following, we will derive implications for solidarity from an empirical inquiry into the daily work of healthcare professionals in Austria. One of the authors of this article, Wanda, accompanied medical treatments in Vienna as part of her ethnographic research and interviewed healthcare workers such as doctors, pharmacists and opticians. It is through their everyday practices that we can better understand what interpersonal and collective (tier 1 & 2) solidarity mean in practice and how they are connected to institutional solidarity (tier 3), namely as enactment and as corrective.

2. Lived Solidarity in the Austrian Healthcare System

Austria’s healthcare system is based on solidarity in the sense that people pay into the system according to their financial means and receive benefits according to their medical needs – regardless of how much they have paid in. Insurance contributions are based on income and deducted from people’s monthly salaries. In addition, a tax-financed support system covers the contributions for people who cannot pay anything, such as those affected from involuntary unemployment, or asylum seekers (LSE, 2017). While the solidarity-based health system is an illustrative example of institutional solidarity (tier 3), solidarity at the other two levels, namely person-to-person solidarity (level 1) and solidarity within groups such as doctors (level 2), offers a more nuanced picture. Healthcare providers have a significant influence on whether the health needs of their patients are met. Unsurprisingly, migrant patients, in particular, often have a harder time getting medically necessary services, partly due to language and cultural barriers. Some healthcare workers compensate for these structural deficits in their everyday work by going beyond the intended level of service and care or even breaking rules in order to do what seems right and just to them.

Examples of lived solidarity

Wanda accompanied a Syrian woman and her child to an Arabic-speaking specialist. During the consultation, the doctor established trust through a mixture of wit and authority. Almost paternalistically, he inquired not only about his patients’ immediate medical concerns but also about other areas of her life such as the language course that the mother was taking, or the child’s school performance. He even made the mother promise to improve her German and the child to learn well. At the end of the consultation, the doctor turned to Wanda. The Syrian woman mentioned that Wanda is from Nuremberg. The doctor was visibly pleased and explained that he had studied in Germany and then had moved to Vienna. He hesitated briefly and then added with a laugh: “as a refugee”. It was not clear whether he saw himself as a refugee from the country of his birth or as a refugee from Germany to Vienna. He then left the treatment room.

In this instance, the doctor implemented – in the sense of making concrete – the spirit of solidarity that is built into the institutional fabric of the Austrian healthcare system. Knowing that his patients have a migration history, and considering himself a migrant as well, he opened the door to wider conversations than medical needs in the narrow sense of the word. He thereby invited his patients to bring into the treatment room – quite literally – wider issues that bothered them, supporting a holistic approach to his patients’ health (probably knowing that the life situation of refugees often is entangled with multiple difficulties).

While healthcare professionals such as this doctor act as the mouths, ears and arms of the healthcare system, solidarity also requires the active closing of structural gaps. An example of how this happens in practice is the following description of a Farsi-speaking general practitioner who takes on gynaecological examinations because there are too few gynaecologists with appropriate language skills in Vienna:

“There are medicines that, for example, only a gynaecologist is allowed to prescribe, yes? I always approve it and add: because of language difficulties; or that [getting an] appointment with the gynaecologist, if she has fungus, would take three months.”

(General practitioner)

The doctor went on to explain that many patients with limited financial means went to see private gynecologists with the respective language skills, despite having to pay out of pocket as their services is not covered by their insurance. On the interpersonal level, this doctor engaged with her patients in a caring way (tier 1). Despite the fact that it costs her time and effort, she took the circumstances of her patients into account and went “the extra mile” to meet their needs. But there is also a group identity element to her practice (tier 2): As a physician, and as a representative of a healthcare system that should pay equal attention to the needs of all, she feels responsible to compensate for the shortcomings of the system.

In addition to the solidaristic practices just described, some healthcare workers try to establish new rules, practices, and norms that improve the situation of the disadvantaged and marginalised. For example, members of the Austrian Medical Association are currently campaigning for more doctors with non-German language skills and increased cultural sensitivity to work within the public healthcare system and improve the care of migrant patients.

It quickly becomes clear that solidaristic practices often take place simultaneously at the interpersonal level and at the level of a collective (tiers 1 & 2). The doctors in our study enact solidarity person-to-person and at the group level, as part of the medical community. The following quote clearly illustrates this simultaneity: With a trembling voice, a doctor told Wanda of a child who died of pneumonia because she and her mother were sent home from the emergency room with painkillers for the child. When the child deteriorated and returned to the emergency room, they had to wait for hours to be seen. Shortly thereafter, the child died in the intensive care unit. “That’s when we felt,” he recounted, “…I felt so guilty with this case at the time because I’m just part of the system. […] That must not happen, something like that must not happen with us, yes?” (medical specialist in Vienna)

The doctor held back tears. He was visibly moved. According to this doctor’s assessment, the tragic consequence had occurred because the medical staff in the emergency room had not interpreted the needs of the patient and her mother correctly. The mother of the child wore a headscarf and spoke broken German. Like many migrants, she was insecure and introverted due to previous discriminatory experiences. The doctor, although having played no part in the tragedy that this family suffered, felt responsible nevertheless: He sees himself as part of this failing system and wants to improve it. He told Wanda of the tragic death of the child as one of the decisive moments for his commitment. Together with colleagues, he now seeks to change the system so that it becomes more receptive and responsive to the needs of disadvantaged groups. For example, he and the other members of his network often refer their patients to specific doctors from whom they expect culturally and religiously sensitive treatment. They also organise information events on these issue through the Austrian Medical Association, which he says are well received by Austrian doctors (tier 2).

Summing up the described instances of lived solidarity, we see three different types of solidaristic practice in our data (Figure 1): In the first (concretising solidarity), healthcare workers act as the mouth, ear, and arm of a solidarity-based healthcare system. They shape solidaristic institutions through their everyday practice. In the second form of solidaristic practice (compensating solidarity), they fill gaps left open by institutionalised solidarity in the healthcare system. Through these practices, solidarity becomes an inherent corrective to the system. A third form of lived solidarity (creating solidarity) goes one step further by trying to create new rules that change the existing norms and instruments (e.g. new laws, but also new criteria for the allocation of resources, etc.).

| What does the healthcare worker do? | Example | |

| Practice 1:

Concretising Solidarity |

Healthcare worker concretises institutional solidarity | Medical specialist inquires not only about medical condition but also about other areas of life, e.g. language course for refugees |

| Practice 2:

Compensating Solidarity |

Healthcare worker compensates the lack of institutional solidarity | General practitioner takes on gynaecological examinations due to the scarcity of Farsi-speaking gynaecologists and – against the guidelines of the medical association – issues free certificates for cash-poor parents |

| Practice 3:

Creating Solidarity |

Healthcare worker tries to create new rules and practices | Advocacy for more multilingual doctors within the public healthcare system |

Lived solidarity – in the forms of concretising, compensating and creating solidarity – can contribute to better care, especially for disadvantaged groups. These lived instances of solidarity help to expand upon person-to-person (tier 1) and group based (tier 2) solidarity (Figure 2). They sharpen our understanding of solidaristic practices within the healthcare system and beyond.

Why do healthcare workers act in solidarity?

Most of the healthcare workers this article focused on are immigrants. That is the case because Wanda’s fieldwork, in accompanying refugees in Vienna to medical appointments, often confronted her with doctors whose native language matched the language of the patients. Seeing this and the solidaristic practices she witnessed during such appointments, Wanda oversampled this group of healthcare workers in her interviews – and we can make no claims about the statistical representativeness (or not) of such practices regarding the wider group of healthcare workers in Vienna, or in Austria. What insights from Wanda’s fieldwork show, however, are the forms that solidaristic practice plays within the healthcare system, and what gaps it fills. It was remarkable to see also that the commonality of being an immigrant was not the only – or not even the most important – commonality that shaped concrete solidarity practice. Instead, it was other things that they had in common with their patients – that one was also a mother or father, for example – that guided the actions of healthcare workers. This is apparent also in the following example: written confirmations of certain medical assessments are subject to a fee. These include medical reports for legal proceedings, but also confirmations for schools or employers about the necessity of sick leave. Some schools have made such written confirmations compulsory – which poses difficulties for poor parents. A general practitioner told Wanda that she considered this practice “unfair”:

“I am a mother myself – and when I call [the school] and say ‘my child is sick’, it means my child is sick. Up to three days, the parents can do it themselves [without needing written confirmation from the doctor]. No parents would call if their child was not sick. I mean, what’s the point, yeah? Sometimes it’s really annoying, yes, because it’s unfair, I think.”

(General practitioner who came to Austria as a child from a Farsi-speaking country)

The injustice that this doctor was addressing was the different treatment of parents whose societal standing is apparently high enough to be believed when they say their child is sick, while other parents need written confirmation to be believed. In addition to being a mother, the doctor based her actions on her sense of justice. Because she felt that the unequal treatment was unfair, she acted in solidarity with the children and their parents: she told Wanda that she regularly calls the school to challenge that a written confirmation (that parents would need to pay for) is required for this particular child. She does not shy away from the emotional effort and time that it takes to deal with the problem. If it cannot be avoided, she even issues appropriate written confirmations free of charge, contrary to the medical association’s stipulation that she has to ask a for a fee. It is important to her to ensure adequate care and to do her job well. Some social groups – due to language barriers, certain previous experiences such as traumatic experiences, cultural differences, low assertiveness, or financial limitations – need more attention to have their health needs met. The solidaristic practices of healthcare workers establish justice in the sense of adequate medical care for all insured persons. Finally, the sense of responsibility of individuals plays a role in motivating people in the health sector. Many of the healthcare professionals that Wanda interviewed take responsibility in order to resolve what they perceive to be unjust or simply wrong.

3. What to do?

We have shown that healthcare workers are important actors of solidarity in the healthcare system. We have distinguished three forms of solidarity, namely concretising, compensating and creating solidarity. The lived solidarity of people in healthcare professions is essential to ensure that the promise of justice for people with upright insurance coverage – to receive the same good medical treatment – is kept for all patients. It is clear that many of these solidaristic practices compensate for institutional failures. Some people, e.g. disadvantaged groups, are not visible in the imagination of those who have created the healthcare system. A look at solidarity in practice draws our attention to these invisibilities. However, the forms of solidarity in practice that we have discussed (Figure 2, Practice 1-3) also make clear that healthcare workers take on high emotional, time-wise, and other costs for their actions.

Despite the important role that the practices of healthcare workers play within solidarity-based health systems, the experiential knowledge of these people has practically no impact on research and policy-making. This needs to change: On the one hand, we need to ensure that lived solidarity in the health system can continue to fill the gaps that a formal institutionalised framework necessarily leaves open. It contributes to better and more equitable health outcomes, especially for disadvantaged populations, but also takes pressure off healthcare workers. Moreover, the solidaristic practices of healthcare workers can show us what other gaps in solidarity exist in the healthcare system that need to be filled and closed by a change of practice and policy.

As a first step, there must be a stronger focus on the solidarity work of the health professions in (basic and applied) research. A systematic recording and evaluation of the experiential knowledge of various health professions will provide information on where there are institutional and structural problems, or where disadvantages occur. In this way, we can determine what actions of healthcare workers should be promoted. This also makes it possible to find out where more or different resources are needed – be it through adjustments to the reimbursable services of the health insurance companies, monetary remuneration or the making available of services such as health navigators. Increased attention to lived solidarity enables us to actively decide what forms of solidarity should be institutionalised (creating practices) or more strongly valued by the system (concretising and compensating practices). The Covid-19 crisis has resulted in a re-valuation of solidaristic institutions, including healthcare systems. Now is a particularly good time to anchor solidarity more firmly as the basis of the healthcare system. To this end, it is important to recognise the lived solidarity in the work of the health professions.

This is a shortened version of Spahl, W., and Prainsack, B. forthcoming. Konkretisieren, erweitern, gestalten: Gelebte Solidarität im österreichischen Gesundheitssystem. In: Hofmann, C. M. and Spiecker gen. Döhmann, I. (Eds.), Solidarität im Gesundheitswesen – Strukturprinzip, Handlungsmaxime, Motor für Zusammenhalt?, Peter Lang Verlag.

References

Lievevrouw E and Van Hoyweghen I (2021) Respect for public healthcare system gives ‘brave Belgians’ the courage to maintain solidarity. https://bit.ly/3sai9Na

LSE Consulting (2017) Efficiency Review of Austria’s Social Insurance and Healthcare System. London. https://broschuerenservice.sozialministerium.at/Home/Download?publicationId=424

Prainsack B (2020) Solidarity in Times of Pandemics. Democratic Theory 7(2): pp.124-133.

Prainsack B and Buyx A (2015) Ethics of healthcare policy and the concept of solidarity. In: Kuhlmann E, Blank R H, Bourgeault L and Wendt C (eds). The Palgrave International Handbook of Healthcare Policy and Governance. New York: Palgrave. 649-664.

Prainsack B and Buyx A (2017) Solidarity in Biomedicine and Beyond. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Prainsack B and Buyx A (2011) Solidarity: Reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics. London: Nuffield Council on Bioethics.