An interdisciplinary gathering of scholars took place at Madeira Interactive Technologies Institute (M-ITI) on October 19-21 2017. We came together to discuss the issues we confront in our work looking at the intersection of remoteness, technology, and self-determination. What began as a plan to write a manifesto ultimately resulted in a hypertext document replete with ambiguity. The structure of the final piece was intended to mirror our booksprint location and site of inspiration – an archipelago of islands, in this case formulated as a series of interlinked but standalone pieces of writing.

This report is being written in the aftermath of a vicious storm which swept the Portuguese island of Madeira – flights cancelled, no one coming in or out. The fisherman’s boats usually dragged up on the wharf had to be relocated to protect them from waves several meters high. A few days later, life more or less went back to normal. The weather, usually a topic reserved for awkward water-cooler small talk in big cities, is a topic of major concern on a remote island, dictating whether the isolation of island life is felt acutely or obscured.

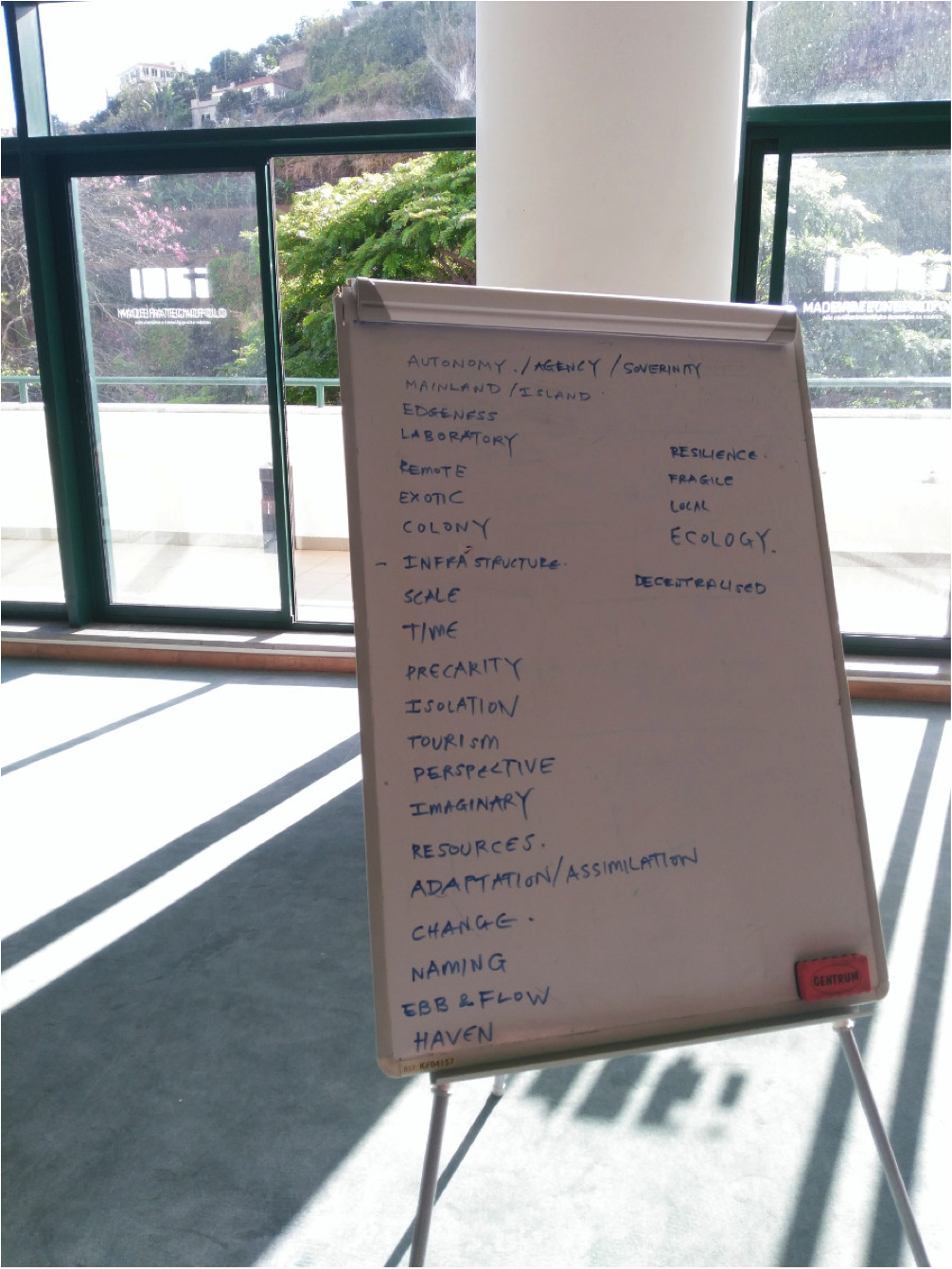

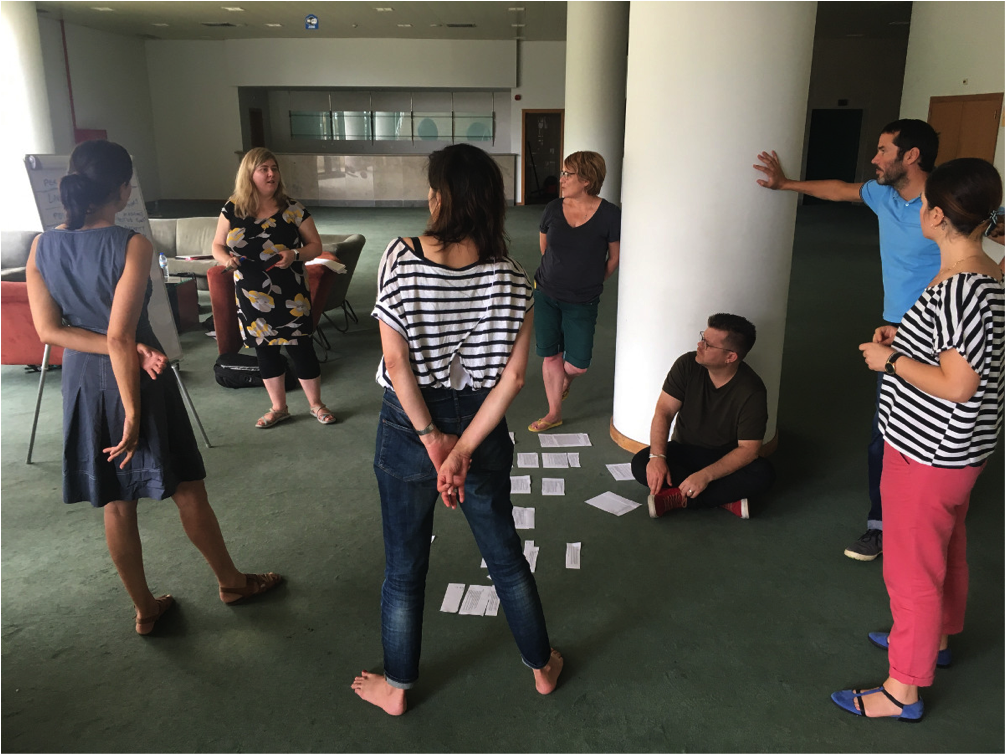

We were fortunate, when we chose to gather in late October of 2017, that the weather was with us, so none of our guests were detained enroute. Together we were a group of eight academics, with five of us from Madeira Interactive Technologies Institute (M-ITI) (Michelle Kasprzak, Gemma Rodrigues, Mariacristina Sciannamblo, James Auger, Julian Hanna), one rural-born Canadian artist (Garnet Hertz), an Irish artist living on a remote Orkadian island (Saoirse Higgins), and an Indo-European design scholar (Deanna Herst). We started our booksprint trying to define the contours of the chosen topic before us – STS and remoteness/islandness. (Figs 1 and 2). We arrived having browsed a series of communally suggested paper recommendations beforehand, featuring STS thinkers such as Susan Leigh Star, Sheila Jasanoff, Ruth Oldenziel, Steven Jackson, and Bruno Latour, as well as Island Studies scholars such as Elaine Stratford and Adam Grydehøj.

Though in our initial planning we entitled the booksprint “Science, Design, and Technology on the Periphery: A Manifesto”, and despite the presence of an expert in manifestoes in the person of digital humanities scholar Julian Hanna, the relativities and ambiguities of our topic soon became clear, putting the case for a manifesto on unsteady ground. In our discussion we were able to define many polarities when thinking of island life or remote living and technology: tourist/local; mainland/island; resilience/fragility, et cetera. These polarities, which may have provided scintillating material for a pointed manifesto, proved difficult to maintain once interrogated further. Ultimately we found more interesting murky corners in the contradictions and overlaps, such as a quasi-aphorism from an anonymous Madeiran local: “There are tourists who visit and tourists who live here”, and the idea of the island’s distinct borders also ultimately acting as threshold. Each concept we explored seemed to have a surface polarity obscuring a deeper complication or paradox.

This complexity also manifested in the final form our writing took on. Inspired by anti-colonial theory and non-binarism, a key element of our explorations looked at how ‘epistemological ecologies’ and diversity could be an antidote to ‘epistemicide,’ the obliteration of locally adapted ways of knowing and doing (de Sousa Santos). Thinking in a non-binaristic way and hoping to present many different aspects of related problems in the area of STS, design, and remoteness/islandness, we created an “archipelago” format for our final publication. We decided to create multiple short texts, each one an “island” in the final larger archipelago. Each island would concern itself with one theme, and within the context of the larger archipelago would find the resonances and references to other concepts. We accepted that within this there would be slight thematic overlaps, but that each island could potentially treat a similar concept with a different perspective. For example, the textual island themed “Mainland/island” looked at power relationships between mainland and island, and specifically at re-examining the Indonesian concept of “goytong rotong”, or reciprocity, as a way of circumventing top-down authority. Other textual islands also looked at power, but addressed this notion in geographical, technological, or cultural ways.

The idea of island as outpost and laboratory became a focal point where histories of technology and sociotechnical imaginaries intersected strongly with the concept of remoteness. In the textual island we developed entitled “Laboratory”, we explored the long history of how islands lend themselves well to becoming sites for technological or social experimentation, or as Schalansky points out: “For empirical research, every island is a cause for celebration, a natural laboratory.” (Schalansky 2010) The constant search for new territory is expressed in the dark visions of techno-libertartians who promote concepts such as seasteading or the colonization of outer space. Techno-libertarians also fetishize islands (natural or created) as providing an ideal incubator for moonshot projects, away from the regulatory structures and taxation obligations of nation states. These principles are made clear in, for example, Wayne Gramlich’s manifesto ‘Seasteading: Homesteading on the High Seas’: “tax avoidance is my pick as the most powerful motivator for the development of sea surface colonization technology.” (Gramlich 1998)

Another key island in our textual archipelago examined the phenomenon of frugal innovation. When materials can take quite some time to arrive, or aren’t available at all, local hacks provide a way to continue to experiment with new designs to common problems. Known as a ‘kludge’ in America, ‘bodge’ in England, ‘jeitinho’ in Brazil, ‘jua kali’ in Kenya, ‘jugaad’ in India, ‘zizhu’ in China and ‘Systeme D ‘in France, this way of creating has resonance far beyond the island context. However, we noted that “Islands serve as a microcosm of the world, reminding us of the global condition of having limited resources – and that ad hoc repairs, whether on an island or on the mainland, is a raw form of design that stands in contrast to the standardized, commodified and generic.” (Kasprzak et al, 2017)

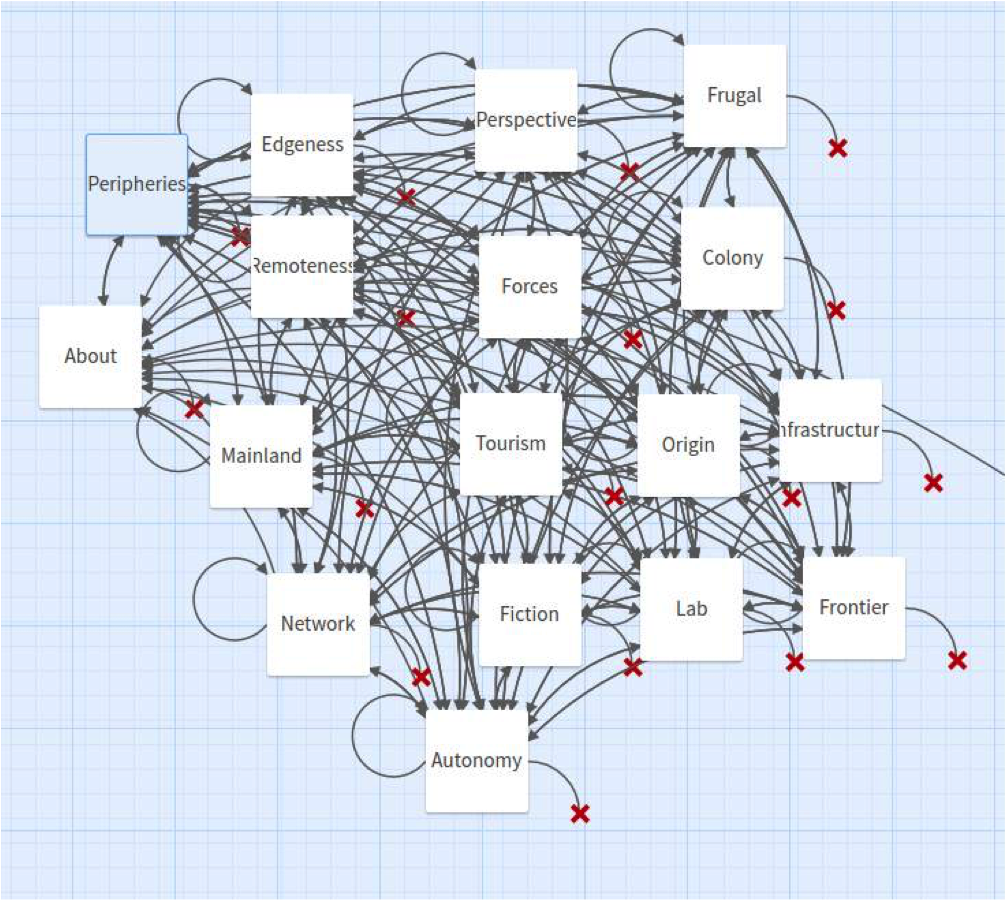

Once we had drafted our series of textual islands, the question remained about how to best present them. Typically a book sprint involves several collaborators working on a digital document which is then published as an EPUB and shared. These results are sometimes printed out as short-run books. In our case, our multiple textual islands lent themselves well to neither an EPUB nor a printed document, and instead we found the hypertext paradigm fit our concept best. Using Twine, an online tool for constructing simple games, we were able to create our archipelago, even including a simple method of wayfinding and navigation in the pages. (Fig 3)

Our event drew to a close, and we continued the work of final editing and sourcing images. Throughout we maintained a commitment to ‘island thinking’ and tried to imagine what the connections were between textual islands. The thematic pieces of writing all belonged together in one archipelago, but it is a network with connections of various strengths among islands. We made choices on where to include links to other islands based on what we believed were particularly strong or relevant thematic connections.

Throughout our process, we continually returned to the notion of how the edges can lead, or be independent, instead of being the isolated backstage, tapped of resources to support a distant metropole. With this final collection of textual islands, we hope to provide a stimulating set of responses to the ongoing issue of technological development and how it benefits and burdens center and periphery in differing ways.

Read the full publication: http://bit.do/periphery