Situating agencies and solidarities in environmental sustainability. Reporting from EASST14 in Toruń, Poland.

My paper and I were to participate in a track called “Situated agency in environmental sustainability”; L2 was its orderly affix in the conference program. It took place in room AB 3.10, on the third floor of the recently built humanities building of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.

There were about 15 of us in the room when the first session of the track started, on September 17 at 10.30 a.m. The two conveners, Brit Winthereik and Ingmar Lippert, both STS scholars from the IT University of Copenhagen, welcomed us to what they qualified as a first step of some yet unknown collaborative work of theirs. We would have four sessions of each 90 minutes; 12 papers that all responded to the call for papers engaging “how people participate in reconfiguring environments”. Responding to the overall conference theme, Situated Solidarities, the two conveners asked us to, throughout the sessions, think about and discuss “to whom we offer what kind of solidarities?”

How do we practice solidarity as (STS) scholars? And where do we situate it? Solidarity with different practices? With different entities…?

The welcome had an open, explorative, positive tone. In contrast to other larger conferences, where sessions are short, time is utterly compressed and collective thoughts are most often cut off as session participants walk out of the room where the papers are given, I felt a relief knowing that I would be able to think continuous thoughts with which to engage in a continuous dialogue and discussion.

Throughout the four sessions a path was paved through a variety of empirical settings; we travelled through corporate carbon accounting, a Chilean copper mine, Swedish corporate care for sustainability, nature-making through coast protection in New Zealand, Greek river expertise, responsible climate adaptation in Denmark, optimization in environmental management in an international NGO, wastewater management in Peru, design and ontology of noise in England, buildings as nature-machines in Norway and Swedish smart grids. The papers were weaved together by the physical setting where they were presented – a teaching aula at a Polish University; curtains, electronically interconnected with the projector, cut the daylight from entering the room, and an air-conditioning system prevented us from feeling the pleasant autumn temperatures in the outside world. We were crafting an academic conference by aligning the material practices with those going on in other rooms next to ours, and by gathering our thoughts and reflections around each other’s papers.

Throughout the path along these many ethnographic sites, a rich landscape of concepts and possible analyses was drawn out for us to tumble and play in: ontic achievements, erroneous environments, making STS travel, care as practice, multiple sustainabilities, infrastructures – and infrastructuring, politics of expertise, governance of natural commons, infraconceptual critique, creative redefinitions, overflows, assemblages and holistic vagueness…

Solidarity was played out as a concept and a notion that shifts the engagement and relation we as analysts / scholars practice in the realities we engage with when we do our work. It may mean shifting the level of commitment towards a less distant form of analysis towards one that is closer to the idea of collective world-making. In the final session, our visionary and realist conveners made us go together in groups and discuss what we had learned from the sessions.

Some of the questions that circulated along the track, and in the final discussions:

- Does reality-making need people who think of reality-making?

- Is there a difference between ontic solidarity and ontological solidarity?

- What comes after being troubled?

- Where is solidarity located? How can we invite people to make social analysis?

- What actually qualifies as critique?

- What kind of treasons are we afraid of?

- What are the connections and disconnects between care – solidarity – critiques? Can we think of scholarly practices in which we shift between these?

- How can design be used as ethnographic method when engaging with environmental controversies; a way to build new relations, physically?

- Can we (scholars) work towards daring to risk or de-stabilize our own position?

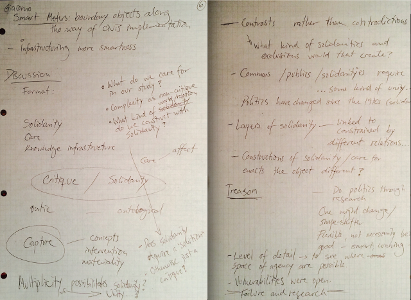

Finally, we opened the curtains, let light in, changed the way of seating and got together in small groups that after a while gathered in one, to summarize the discussions and make the reflections collective. Instead of summing up the contents of the discussion, I leave you a glimpse of the notes I took of our collective reflections:

Coffee breaks, two-hour lunches, plenary sessions, and a spectacular social event in the Toruń fort made our conference track cross those of other participants, and weaved the EASST experience together as a dense meshwork of presentations, discussions, sharing and reflections. I appreciated these spaces, which made the conference a place where it was possible to meet and connect with new and already known people.

When returning to Denmark, by train, with my papers full of notes and ideas, track convener Ingmar Lippert – a passionate STS scholar and activist – was sitting in front of me, clearly satisfied with the EASST experience: “this is the third time I come to this conference feeling genuinely at home, it is like my community”. I understood why, and thought that I look forward to my path crossing that of others at future EASST conferences.

Author Info

Astrid O. Andersen is postdoc at the Department of Anthropology at University of Copenhagen; her research centres on human-environmental relations. Astrid O. Andersen is postdoc at the Department of Anthropology at University of Copenhagen; her research centres on human-environmental relations.astrid.andersen@anthro.ku.dk |