Liveable futures1 bring into question the conditions that make human and more-than-human lives possible and provide these with prospects. Such futures are made of multiple elements, including knowledge infrastructures (KIs). Knowledge infrastructures, by creating and recreating objects, categories and relations, make important contributions to frameworks that make some forms of life intelligible, and other forms of life precarious. It is in this sense that in much of our work, we seek to articulate how KIs can contribute to liveable futures.

Because liveable futures are very much a project that is to be achieved in practice, the phrase is also at the core of engagement activities of the Knowledge Infrastructures Department and of the faculty of Campus Fryslân at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands), where we have launched an annual Liveable Futures Festival and a book series with Amsterdam University Press. The festival and series engage different colleagues and publics and constitute occasions to further reflect on and develop this concept through interaction with a diversity of stakeholders. Liveable futures help articulate what is non-negotiable for survival and what makes life worth living. It opens up a space to share different needs and different matters of care. In our experience so far, it supports interactions about the kinds of ‘present’ in which lives are lived and how these might continue (or not) in the future– and it does so in ways that are more generative than discussions framed by catastrophic or utopian narratives.

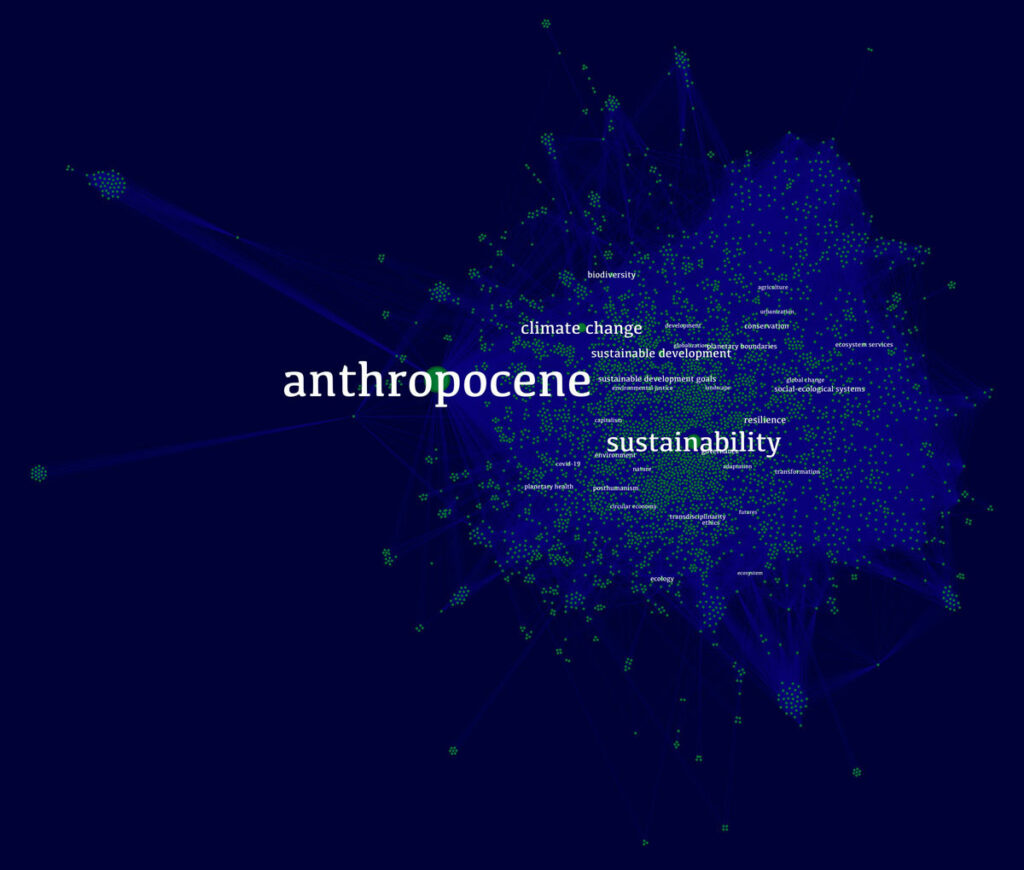

By collectively writing about liveable futures, we, the authors, have consolidated our understanding of the term and identified aspects where our emphasis varies—both equally important negotiations. We have also shared how the phrase has a different valence, resonating with some of the other languages in which we work (futuro vivible, avenir vivable). And we have debated whether the variability in the term liveable is politically risky, as it potentially builds in too much room for manoeuvre. By sharing the phrase with the EASST Review readership, we hope to stimulate further interaction and engagement with the project to which we are committed: building knowledge infrastructures that can support the knowledge urgently needed for liveable futures. Other terms such as sustainability or Anthropocene are the most common labels to orient action towards improving conditions and conveying a sense of crisis. Before introducing liveable futures, we first take a look at how these two terms work, and consider why a new label really is necessary.

Is sustainability more of the same?

The term sustainability has travelled across different fields over the past 50 years, to become a very prominent term in everyday parlance and a ubiquitous qualifier to a wide range of activities, institutions, goods and services.

As it is most frequently defined, sustainability is about continuing and lasting prosperity, and reliance on environmental resources to achieve this prosperity. It is a contested concept (Washington, 2015), and is strongly associated with preservation of vested interests rather than transformation of exploitative systems. Part of this negative connotation has to do with the close association of sustainability with ‘sustainable development’ which is in turn connected to economic growth. Sustainability, in the context of development, does not convey the urgency of the current problems nor the need to do much more than sustaining current conditions. This stance that reinforces the status quo is visible in the well-known Brundtland (1987) report (WCED, p. 37):

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Implied in this definition is a highly uneven burden, with regards to sustainability. It stresses that further development is what must be achieved sustainably, thereby leaving developed countries and their structural unsustainability out of the picture. Some years later, a very similar elision would be made extremely clear through the intervention of Agarwal and Narain (1991), demanding distinction between essential and luxury emissions as a necessary step toward equity in addressing climate change. In other words, a focus on sustainable development has served to curtail cumulative responsibilities of developed countries—tainting sustainability as a framing concept.

Furthermore, most writing on sustainable development assumes, implicitly or explicitly, that economic growth is the key to development (Washington, 2015). The centrality of economic growth therefore aligns much sustainability discourse to neo-liberal modes of social organisation and extractive relations to the environment-as-resource. Both sustainability and sustainable development originally thrived at the intersection of ecology and political discourse, but have increasingly been taken up by business, where it is “associated with efficiency, profitability and even growth” (Vasseur and Baker, 2021). The term green growth is a related label that attempts to reconcile the impossibility of continued growth based on exploitation of finite planetary resources (Wijkman and Rockström, 2012), the starting point to well-known work on donut economics (Raworth, 2017).

While some remain optimistic about the possibility of decoupling the term sustainability from sustainable development and growth (Washington, 2015), the concept of sustainability is too closely connected to resource thinking, an approach that sees nature and the material world as assets to be exploited (Turnhout, 2024). It relies on the colonisation of nature (Banerjee, 2003), and comes from a tradition that distinguishes, disconnects and often opposes natures and humans, reserving agency exclusively for the latter, as critiqued by Haraway (1991, p. 198):

Nature is only the raw material of culture, appropriated, preserved, enslaved, exalted or otherwise made flexible for disposal by culture in the logic of capitalist colonialism.

The interdependence of culture and nature, of society and the environment needs to be emphasised, as does the move away from the (post-hoc) distinctions and binaries of modernity, in order to understand highly situated, unequal access to ‘resources ‘and need for radical action (Haraway, 2015).

Sustainability is therefore problematic in a number of ways. First, in the way it orients to action. If sustainability calls for change, then it is only as a breaking force to slow down the scope of exploitation today, to ensure exploitation in the future. Second, it foregrounds an economic logic, for example in the articulation of sustainability as the achievement of a balance between the distinct elements of environment, society and the economy (sometimes expressed with the shorthand ‘people, planet, profit’). This is objectionable because they set economics apart, as though it were not part of society (Smythe, 2014), and as though economics is confined to industrial-capitalist practices and values (Gibson-Graham, 1996). Finally, and most fundamentally, it obfuscates that currently (and even arguably in the 80s), the differentiated consumption patterns across the planet amount to overshooting of the earth’s resources (see https://data.footprintnetwork.org/#/) –a situation that calls for transforming, not for sustaining.

Who actually lives in the Anthropocene?

A second dominant term, the Anthropocene, is the ‘scientific proposal that the Earth has entered a new epoch as a result of human activity’ (Lorimer, 2017, p. 117). In contrast to sustainability discourse, it does foreground the interaction rather than the distinction of the social and the natural. It signals, by its evocation of an epochal shift, the scope and gravity of current crises. It is also a term that has currency across different constituencies, thereby providing a common banner under which to unite (Hastrup, Münster, Tsing, and Bubandt, 2022). It is furthermore a way to highlight the evidence for disruption at the scale of Earth systems through (human) industrial and colonial activity. However, the term is also criticised along different axes. Its anthropocentrism is blatant (Brannen, 2019), that is to say, the way it centres Anthropos as the deeply problematic category of ‘human’ and the system of exclusions on which the concept relies (Yusoff, 2018). By insisting on Anthropos as a uniting label, in its lumping of all of humanity into a single actor. Anthropocene evacuates huge differences in the relation, responsibility and vulnerability of those who might be subsumed to this all-encompassing Anthropos (Chakrabarty, 2015; Haraway, 2015; Todd and Davis, 2017), and in so doing fails to acknowledge the ontological and epistemological diversity in human-nature relations (Descola, 2013; Vilaca, 2016). As a diagnostic label, Anthropocene erases crucial distinctions and reveals a ‘global’ problem at a scale where action and agency are hard to imagine. It can only be embraced via highly complex mechanisms of abstraction, of which the IPCC reports are emblematic. The epochal scale also foregrounds the unprecedented status of the current crisis, highlighting universal human frailty and obscuring how forms of power are maintained, even as solutions are articulated (Whyte, 2020).

A starting point that lowers the threshold for action is needed, a more accessible, humble future that recognizes the importance and value of everyday mundaneness. Our proposal is therefore to use ‘liveable futures’. To provide a better invitation: ‘what is a liveable future for you, with others?’ instead of ‘what to do about the Anthropocene?’

Futures…

The proposal for a label of ‘liveable futures’ as a banner under which to galvanise imagination and care as key forms of action therefore aims to avoid some of the pitfalls in the terminology of sustainability and Anthropocene. The components liveable and future work together to evoke both possibility and need for action.

The term future emphasises that there are prospects, it stresses the indeterminacy of what is to come and the possibility to “probe, interrogate and play with futures that are plural, non-linear, cyclical, implausible and always unravelling” (Salazar, Pink, Irving, and Sjöberg, 2017, p. 2). The term future serves as a necessary reminder of the increasingly frequent implementation of algorithmic shutting down of the future through predictive reliance on past data (Beaulieu and Leonelli, 2021), or through discourses of inevitable futures (Schiølin, 2020). Conversely, much of techno-science is oriented to the future and especially towards an idealized ‘future perfect’ based on “hopes that… current hardship will have been the necessary precursor to future prosperity” (Hetherington, 2016, p. 42). It is clear that the future plays an important role in constituting the present (Brown and Michael, 2003).

There is also nothing grandiose about ‘liveable futures’, it is rather something mundane than heroic. We consider these to be advantages, because they do not evoke emergencies and crises. The framing of current situations as emergencies and crises is predominantly intended to spur action—understandably, these are worrying times. But the invocation of emergency (Murphy, 2018; Papadopoulos, Bellacasa and Tacchetti, 2023; Whyte, 2020) can be used to create hierarchies of values, subsuming justice, reciprocity, care and deliberation. Change over time can be understood through the ability to remember a past and project a future (Conty, 2018). Instead, such epistemologies of crisis also focus on a present that is unlike any past, hence precluding the use of lessons learned from the past (Whyte, 2020).

Against this tendency, liveability, in its humble everydayness, is meant to be a reminder that relations of all kinds exist, may need repairing, and certainly require care. Finally, in our phrase liveable futures, these futures are plural, insisting on plurality, both in terms of outcomes and of experience. When the very possibility of the future is put into question, this triggers a defensive stance that is neither creative nor hopeful and it reinforces the notion that ‘nature’ or ‘the environment’ are hostile, as Amin (2013) implies (as cited in Barua, 2021, p. 1481):

Resilience infrastructures are part and parcel of emerging forms of neoliberal biopolitics that is ‘catastrophist’, one where ‘the future is increasingly being cast as unpredictable and dangerous’ and where ‘preparedness’ becomes the watchword.

Furthermore, there may be a great diversity in experiences of the futures to come, a possibility that again, is shut down by crisis thinking that funnels efforts into saving the current state of affairs and may “obscure how everyone one else may experience today’s world” (Whyte, 2020, p. 62). The plural form emphasizes multiple experiences and works as a reminder that the task is not to find the best possible future, but rather to open up space for different ways of achieving liveability in different forms, adapted to rich localities.

…that are liveable

If the future is open, it is accompanied by ‘liveable’, as a normative qualifier. Liveable futures are scenarios in which the possibility of liveability is envisioned. Liveable futures are neither objects nor certainties, but sets of conditions that can refer to situations good enough to live properly, to describe a desirable and enjoyable future, or to describe the minimum needed for survival. This may be different across forms of life; as Mette Nordhal Svendsen notes in her analysis of the dynamics of imagined futures, a key question is what is assumed to be the “common good” (Groth-Jensen, Svendsen, and Snell, 2023). Liveable can therefore have a range of connotations, spanning endurable, survivable, suitable for living in, inhabitable, agreeable, among other common meanings. Such a sliding scale seems appropriate for these uncertain times. The term liveable futures indicates that the possibility of survival—and therefore also the possibility of NOT living on—has to be taken into careful account. While liveability has been turned into an indicator 2, liveable futures is neither a measurable object (like growth), nor a certainty, nor an assessment (like sustainability), but a situation to live in. Such a sliding scale might be risky: it provides room to manoeuvre for different agendas, and might seem to lack the strength of a clear goal. However, clear goals can only be reached in the context of strong relations of accountability, of commitment. Liveable futures stress the conditions in which these relations thrive, so that negotiations and commitments to liveability can emerge.

Liveable, especially in the British spelling, has a conspicuous suffix. The particle -able has the meaning of ‘capable of’. Liveable therefore invokes the capability for living. Capability for life is not a feature of the organism, but of the organism in interaction with its context. For Butler (2010), liveable is important to “move away from a focus on individualism and the protection of life in and of itself and directs attention to the conditions which maintain life, which either enhance or reduce its precariousness in a particular location at a particular time” (McNeilly, 2016). For Butler (2010), liveability is undergirded by the conditions that ensure physical persistence and conditions of ‘social intelligibility’, the possibility of living a life that counts, that is meaningful.3 Conversely, frameworks (racism, sexism) that increase precarity of certain lives by making them unintelligible (McNeilly, 2016), such as those of migrant or transgender persons, decrease the liveability of certain lives3, rendering them ‘wasted’ because of their perceived ‘uselessness’ for economic (industrial-capitalist) progress (Bauman, 2003).

While Butler has elaborated the term liveable as an important criterion for human life (Butler, 2010), we propose to extend it to all forms of life to avoid falling in the anthropo-centric trap that also surrounds the Anthropocene. Instead we embrace the challenge of formulating what a liveable life for an insect or microbe or mushroom might be as important and generative of better living-with non-humans in a multispecies planetary environment. While precarity—that which threatens liveability— is defined by Butler (2010) as “politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks of support and become differentially exposed to injury, violence, and death” (p. 25), precarity can also be environmentally induced and experienced, affecting non-humans.

Whether the plurality of ‘liveable’ is potentially also a weakness is the object of debate–also among the authors. On the one hand, ‘liveable’ can be co-opted into dominant, often neoliberal discourses. Perceptions of how to classify ‘liveable’ can be diverse, and may even contradict each other. Debates about ‘invasive species’ are indicative of such a potential tension, valuing the movement and presence of some species, while others are threatened, often following global hierarchies and colonial flows (Cottyn, Devliege, and Cahn, 2023; Kirbis, 2020). Disagreements about the creation of ‘liveable’ environments are also central to broader conservation discourses, which often side-line, actively exclude, and at times forcibly relocate and actively devalue some (human) lives over those of others, as exemplified in global critiques of indigenous hunting practices (Hobbis, Soete, and Hobbis, 2024) or the Half Earth vision for conservation (Büscher, Fletcher, and Brockington, 2017). On the other hand, this plurality and conceptual openness of ‘liveable’ opens up a space for interaction about ‘liveable futures,’ one that has the capacity to account for human and planetary diversity, including the inequalities and systems of exploitation that have, so far, shaped too much of the past, present and visions for the future. The phrase ‘liveable futures’ signals an ethically and politically normative aspiration. It serves to express the need of dealing with serious problems to ensure futures and stresses that much is at stake—a humble aspiration towards the possibility of life that has to be developed in caring interaction, with awareness of trade-offs.

Endnotes

(1) As a phrase, we have come across ‘liveable futures’ in some urban planning contexts, which stresses its relevance to everyday life.

(2) The Economist Intelligence Unit has a liveability index of cities:

The concept of liveability is simple: it assesses which locations around the world provide the best or the worst living conditions. Assessing liveability has a broad range of uses, from benchmarking perceptions of development levels to assigning a hardship allowance as part of expatriate relocation packages. Our liveability rating quantifies the challenges that might be presented to an individual’s lifestyle in any given location and allows for direct comparison between locations” (Global Liveability Index, 2022).

(3) See discussion of phrase ‘all lives matter’ and of Butler’s position in Victor (2016).

Works Cited

Agarwal, A. and Narain, S. (1991). Global Warming in an Unequal World. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment.

Banerjee, S. B. (2003). Who Sustains Whose Development? Sustainable Development and the Reinvention of Nature. Organization Studies 24 (1), pp. 143–80. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024001341.

Barua, M. (2021). Infrastructure and Non-Human Life: A Wider Ontology. Progress in Human Geography 45 (6): 1467–89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132521991220.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts. Cambridge: Polity.

Beaulieu, A. and Leonelli, S. (2021) Data and Society: A Critical Introduction. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Brannen, P. (2019). The Anthropocene Is a Joke. The Atlantic. August 13, 2019. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/08/arrogance-anthropocene/59579/

Brown, N. and Michaels, M. (2003). A Sociology of Expectations: Retrospecting Prospects and Prospecting Retrospects. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 15 (1), pp. 3–18.

Butler, J. (2010). Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? Reprint edition. London: Verso.

Büscher, B., Fletcher, R. and Brockington, D. (2017). Half-Earth or Whole Earth? Radical ideas for conservation, and their implications. Oryx. 51(3), pp. 407-410.

Chakrabarty, D. (2015). Lecture: The Human Condition in the Anthropocene, The Tanner Lectures in Human Values. Yale University. Available at: https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_resources/documents/a-to-z/c/Chakrabarty%20manuscript.pdf.

Conty, A. F. (2018). The Politics of Nature: New Materialist Responses to the Anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society 35 (7–8), pp. 73–96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418802891.

Cottyn, H., Devliege, L. and Cahn, L. (2023). Life Out of Place: Revisiting Species Invasions. Introduction to the Special Issue. Anthropocenes – Human, Inhuman, Posthuman, 4(1), 1. Available at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/ahip.1433

Descola, P. (2013). Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gibson-Graham, J.K. (1996) The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Global Liveability Index (2022). [Online]. Available at: https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/liveability-index-2022.pdf/ [Accessed 29 April 2024].

Groth-Jensen, L., Svendsen, M. N., and Snell, K. (2023). Strategies on Personalized Medicine and the Power of the Imagined Public. New Genetics and Society 42 (1), e2260939. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2023.2260939.

Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin. Environmental Humanities 6 (1), pp. 159–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

Hastrup, K., Münster, U., Tsing, A. and Bubandt, N. (2022). Afterword. Troubling Methods in the Anthropocene: A Roundtable Discussion. In Bubandt, N., Oberborbeck Andersen, A., and Cypher, R.(Eds). Rubber Boots Methods for the Anthropocene. Doing Fieldwork in Multispecies Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 371–410.

Hetherington, K. (2016). Surveying the Future Perfect: Anthropology, Development and the Promise of Infrastructure. In Harvey, P., Bruun Jensen, C. and Morita, A. (Eds). Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion, pp. 40–50. London: Routledge.

Hobbis, S., Soete, A. and Hobbis, G. (2024) Platformizing the hunt for dolphins: Beyond industrial-capitalist encounters with Nature 2.0. Geoforum 149, 1-9.

Kirbis, A. (2020). Off-centering empire in the Anthropocene: Towards multispecies intimacies and nonhuman agents of survival. Cultural Studies, 34(5), 831-850.

Lorimer, J. (2017). The Anthropo-Scene: A Guide for the Perplexed. Social Studies of Science 47 (1), 117–42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312716671039.

McNeilly, K. (2016). Livability: Notes on the Thought of Judith Butler. May 26, 2016. Critical Legal Thinking Blog. [Online]. Available at: https://criticallegalthinking.com/2016/05/26/livability-judith-butler/ [Accessed 29 April 2024].

Murphy, M. (2018). Against Population, Toward Afterlife. In Clarke, A. E., and Haraway, D. J., (Eds), Making Kin, Not Population. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Prickly Paradigm Press, pp. 102–24.

Papadopoulos, D., Puig de la Bellacasa, M. and Tacchetti, M. (Eds.). (2023). Introduction: No Justice, No Ecological Peace: The Groundings of Ecological Reparation. In Ecological Reparation, Bristol, Bristol University Press, pp. 1–16. Available at: https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/display/book/9781529216073/int001.xml.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Salazar, J.F., Pink, S., Irving, A. and Sjöberg, J. (Eds). (2017). Anthropologies and Futures: Researching Emerging and Uncertain Worlds. London: Bloomsbury

Schiølin, K. (2020). Revolutionary Dreams: Future Essentialism and the Sociotechnical Imaginary of the Fourth Industrial Revolution in Denmark. Social Studies of Science 50 (4), pp. 542–66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312719867768.

Smythe, K. R. (2014). An Historian’s Critique of Sustainability. Culture Unbound 6 (5), pp. 913–29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.146913.

Todd, Z., and Davis, H. (2017). On the Importance of a Date, or, Decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 16 (4), pp. 761–80.

Turnhout, E. (2024). A Better Knowledge Is Possible: Transforming Environmental Science for Justice and Pluralism. Environmental Science & Policy, 155 (May): 103729. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103729.

Vasseur, L., and Baker, J. (2021). What Is Sustainability? 10 October 2021. Brock University Blog. [Online]. Available at: https://brocku.ca/unesco-chair/2021/10/10/what-is-sustainability/.

Victor, D. (2016). Why ‘All Lives Matter’ Is Such a Perilous Phrase. The New York Times, 15 July 2016. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/16/us/all-lives-matter-black-lives-matter.html.

Vilaca, A. (2016). Praying and Preying: Christianity in Indigenous Amazonia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Washington, H. (2015). Is ‘sustainability’ the Same as ‘Sustainable Development’? In Kopnina, H. and Shoreman-Ouimet E. (Eds). Sustainability. London: Routledge.

Whyte, K. P. (2020). Against Crisis Epistemology,. In Hokowhitu, A., Moreton-Robinson, L., Larkin, S. and Andersen, C. (Eds). Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies London: Routledge, pp. 52-64.

Wijkman, A., and J. Rockström (2012). Bankrupting Nature: Denying Our Planetary Boundaries.London: Routledge.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) (1987). Our Common Future, Brundtland Report. [Online]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/medien-und-publikationen/publikationen/nachhaltige-entwicklung/brundtland-report.html. [Accessed 29 April 2024].

Yusoff, K. (2018). A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Author biographies

Anne Beaulieu is Aletta Jacobs Chair of Knowledge Infrastructures at Campus Fryslân and holds a PhD from Science and Technology Dynamics at the University of Amsterdam, in The Netherlands. Her work focuses on complexity and transformation in knowledge infrastructures, with particular attention to the creation and circulation of knowledge for liveable futures. She is co-author of Data and Society: A Critical Introduction (Sage, 2021), of Smart Grids from a Global Perspective (Springer Publishing), and of Virtual Knowledge: Experimenting in the Humanities and Social Sciences (MIT Press). She has published widely on the significance of ethnographic methods for the study of data practices. In 2023-24, she was joint fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study and of the Data Science Centre at the University of Amsterdam. Between 2018 and 2022, she co-coordinated the PhD training network of the Netherlands Graduate Research School of Science, Technology and Modern Culture (WTMC). Beaulieu is editor-in-chief of the series Liveable Futures at Amsterdam University Press.

Efe Cengiz (he/him) is a PhD researcher at University of Groningen, Campus Fryslan. His work concerns the epistemic, ecological and socioeconomic injustices and more-than-human futures in the making in olive groves of Turkey’s Aegean region. His teaching focuses on global monitoring infrastructures’ relations with social and epistemic injustices. He’s also a board member of WTMC (Netherlands Graduate Research School of Science, Technology and Modern Culture) and an editor of the political theory e-zine metapolitik.net.

Raul Cordero Carasco is assistant professor at Campus Fryslân, University of Groningen. His background is in engineering and natural sciences, and his research crosses traditional disciplinary boundaries. Raul has worked on climate data, climate change, renewable energies, and the effect of pollution on the biosphere (including on humans). He is currently working on better understanding climate-fueled compounds and cascading climate extremes. Since 2021, Raul has been a member of the International Ozone Commission (IO3C), one of the special commissions of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics. From 2020, he is a delegate to the Geosciences Group of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). From 2017, he is a member of the Steering Committee of the Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Composition Change (NDACC), endorsed by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). Since 2016, Raul has served in the Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) on Ozone and UV Radiation of the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW), a program of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

Dr Selen Eren is an interdisciplinary social scientist working on the politics of environmental science and biotechnologies targeted to address pressing environmental crises, with expertise in science and technology studies (STS) and a focus on multispecies, transdisciplinary, and interventionist approaches. She currently works as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Oulu, Finland, where she investigates the role of microbes in achieving a sustainable bioeconomy. She is a co-founder of ‘iris‘, a crowd-sourced online Turkish encyclopedia of STS terminology. Her PhD research, at the University of Groningen, Department of Knowledge Infrastructures, was on the scientific knowledge production process of a group of ecologists working on the rapid decline of the Dutch national bird. In her dissertation, she focused on transforming the relationship between researchers, birds, and societal knowledge actors into a more equitable and actionable one.

Sarah Feron is Assistant Professor of Climate Change and Energy Transition at Campus Fryslân, University of Groningen. She is intrigued by the question of how climate change is having an impact on our planet and our society, and how the climate and energy systems interact. Sarah’s other passion is Antarctica, where she did fieldwork several times. With the @antarcticacl team, we study the role of Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere climate. She studied international business administration in Vienna, worked as a consultant for 6 years in Madrid, then did a PhD at the Faculty of Sustainability at Leuphana University in Germany, on the factors that foster or inhibit the sustainability of off-grid solar systems in South America. She has worked at the Department of Physics at University of Santiago de Chile and at the Jackson Lab at Stanford University where she worked on topics related to climate change and energy, as well as on predicting methane emission from natural systems.

Matilde Ficozzi is a research assistant at Tantlab, the techno-anthropology lab, in Aalborg University Copenhagen. Her research interest lies in the intersections of anthropology, controversy mapping, digital methods, arts, and communication.She is affiliated with the Algorithms, Data and Democracy research project where she is investigating the role of AI in different social spheres to explore issues of knowledge production and public involvement, how technologies get inscribed in different practices, and how we make sense of them.

Dr Carol Garzon-Lopez is assistant professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands. She is a Colombian researcher and the director of Verde Elemental, a website in Spanish, dedicated to promoting and disseminating knowledge in ecology and conservation for Latin America. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Fondazione Edmund Mach (Italy), where she provides expertise on the use of remote sensing tools and integrative approaches for species distribution modeling as part of the European Union Biodiversity Observation Network project. Her scientific interests include ecosystem ecology and the use of spatial tools for research on conservation in the tropics. She holds a Master’s degree and Ph.D. from Groningen University, Netherlands. During her Ph.D. she studied the determinants of the spatial distribution of tree species in a tropical forest in Panama, at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, where she has also collaborated in education and public communication.

Ruth Howison is senior researcher at the Knowledge Infrastructures Department and at Birdseye, University of Groningen. She has a diverse ecological background ranging from spatial ecology to fundamental and experimental ecology. Currently, she uses big data – such as remote sensing technologies combined with advanced statistics – to understand human impact on ecosystems across the East- Atlantic Flyway (The Netherlands to West Africa). She is interested in developing spatio-temporal analytical tools that track fine-scale changes in ecosystems at landscape scales. A major focus of her work is on the spatial ecology of migratory birds as sentinels for sustainable agriculture.

Clarisse Kraamwinke is a PhD candidate at the University of Groningen. Her project at Campus Fryslân is on the ability of Frisian soils to perform the main five soil functions and services, namely, climate regulation, nutrient cycling, water storage and purification, habitat provision and biomass production. She has published on planetary limits to soil degradation and is committed to sharing her knowledge about the role of soils in environmental dynamics and climate change through teaching and outreach activities.

Maarten Loonen is associate professor at the Arctic Centre of the University of Groningen. As a polar ecologist, he has been studying Arctic migratory birds and changes in their living conditions and focuses on consequences of climate change on geese, seabirds, vegetation and insects. His study area is located on Spitsbergen/Svalbard in the largest international multidisciplinary research village Ny-Ålesund in the fastest warming area of the world. He is manager of the Netherlands Arctic Station and has organised the two largest Dutch Arctic expeditions, SEES.nl. By teaching a course on climate change at Campus Fryslân, he has become an expert in global consequences of arctic amplification. With his teaching and outreach he has become well-known in The Netherlands for his appeal for a change and climate change mitigation.

Marije Miedema is an interfaculty PhD candidate (STS and Media Studies) with a background in the visual arts at the University of Groningen. In collaboration with a theater collective, and local archival institutions, she ethnographically researches the future of our personal digital heritage in a community center. From a critical data and archival studies perspective, she asks for whom do we preserve and at what (environmental) cost? Marije is also a board member of WTMC (Netherlands Graduate Research School of Science, Technology and Modern Culture) and editorial assistant for the Liveable Futures book series at Amsterdam University Press.

Dario Rodighiero is an Assistant Professor of Sciences and Technology Studies at the University of Groningen, serving the multidisciplinary Campus Fryslân faculty at the Knowledge Infrastructure department. At the faculty, Dario coordinates the Data Wise minor to introduce students to data science and social challenges, while also teaching data and visual literacy within the Bachelor’s program in Data Science and Society. Maintaining affiliations with Harvard University, he acts as a principal at metaLAB (at) Harvard, delving into arts and humanities, and holds a position as a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, focusing on controversy mapping. Dario specializes in knowledge design, critical data, and digital humanities, mapping scientific organizations and cultural institutions. His approach allows him to bridge gaps between diverse fields, serving as a mediator for inter-disciplinary projects and initiatives. With Metis Press, Dario authored the book Mapping Affinities: Democratizing Data Visualization. EPFL awarded him a Ph.D. in Sciences after attending the doctoral program in Architecture and Sciences of the City. Over the years, he has held positions at MIT, Sciences Po, Panthéon-Sorbonne University, and the European Commission, lectured at CERN and Ars Electronica, and exhibited at MAXXI and Harvard Art Museums.