Collaboration between Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) and the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (AHSS) is essential if we are to produce science and technology that is able to respond to future sociotechnical challenges. However, interdisciplinarity raises some important questions: How do interdisciplinary teams come together? Where does interdisciplinary funding come from? How can a shared language be developed? What defines successful collaboration? And crucially, how do we address asymmetries of power between disciplines?

There are around 4,200 postdoctoral researchers at the University of Cambridge, but only about 10% are based in the AHSS schools. Furthermore, the demands of disciplinary excellence often overshadow interdisciplinary efforts, making it difficult to negotiate between fields or even create teams with mixed backgrounds or approaches. To explore the tensions and opportunities inherent to research that takes place in the interstitial spaces between fields, a recent STS Cambridge Network (SCaN) event aimed to initiate a conversation about interdisciplinary willingness, challenges and potentials.

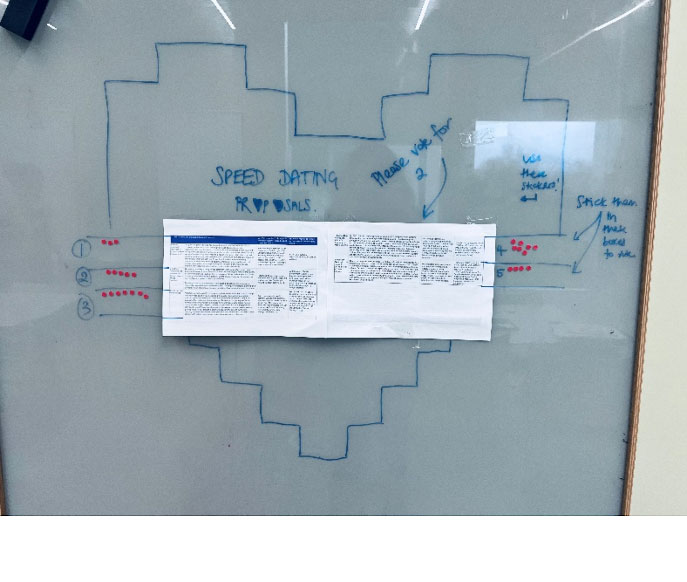

Taking place on 6 February 2025, the Valentine’s-themed speed-dating event invited participants to find their ‘STEM–AHSS soul-mate’ and co-create a research mini-proposal, with a prize for the proposal judged the strongest by a panel of judges. The competition generated 5 collaborative proposal submissions, and was part of a broader event titled Where is the Human in the Data? Bridging STEM and AHSS Hearts & Minds, which also featured two expert panels and a presentation on interdisciplinary funding mechanisms.

Over 60 participants and 14 speakers explored how AHSS and STEM researchers can work together to shape ethical, innovative, and socially impactful research. This article contains our reflections on the lessons that emerged from our conversations, which suggested that successful collaboration requires cultivating a shared language, nurturing long-term relationships, and a strong focus on real-world challenges.

What speed-dating taught us about collaborative working

The speed-dating event began with a group of early career researchers (ECRs) stepping into a bright, unfamiliar room. They were asked to choose a global theme to work on from the sheets of paper laid out before them, bearing words like ‘change and loss’, ‘tech’, ‘resources’, ‘people’, and ‘health’. They moved cautiously at first, gravitating toward topics within their disciplinary comfort zones. STEM researchers clustered around tech and resources, while those from AHSS leaned toward people and health. Their choices reflected both their training and the discursive habits of their fields. That is, the mostly-unspoken conventions that determine how problems are framed, which questions are asked, and what counts as relevant knowledge.

We then prompted the groups to engage with these topics through the lens of a specific global challenge. For instance, by considering biodiversity loss as a matter of change and loss. This shift unsettled the initial arrangements. Participants moved around, regrouped, and redefined their focus. Some found it difficult to commit to one category. Taking one example, if you are interested in how uncertainty and political instability affects the food supply chain, should you join the resources group, or change and loss? The act of choosing – physically and intellectually – became a moment of reflexivity: how do categories constrain what is thinkable, and therefore researchable?

Disciplinary affiliations were less rigid than expected; the boundaries more porous. We had asked participants to self-identify as STEM, AHSS, or BOTH during registration. We quickly realised the third option was essential. Many ECRs were already working across disciplinary lines and did not want to be pigeon-holed as one thing and not the other. Indeed, defining the event as AHSS meets STEM might already have put people off – filtering out potential attendees who did not see themselves singularly as either STEM or AHSS, or who did not want to categorise themselves at all.

Back in the room, the focus on specific global challenges prompted the ECRs to rearrange themselves into more diverse cross-disciplinary groups. The researchers briefly introduced themselves before launching into a round of fast-paced, paired networking. The room quickly filled with the noise of laughter, with gesturing hands, and animated exchanges. We challenged each group to co-design a collaborative research proposal geared towards their chosen global challenge, and to identify a potential funding route. Beyond the prize we offered, we hoped they might also discover something more enduring: a new research collaborator, or even a ‘soulmate’ for future projects.

By the end of the session, five proposals had been crafted – one from a trio who insisted their collaboration worked best as a threesome rather than restricted to a pair. As the organisers began to pack up, many participants stayed on to continue their conversations, sketch ideas and build momentum. What had started as a structured exercise had become something more open-ended and more hopeful: an experiment in the possibilities of interdisciplinary connection. We know that at least one collaboration has since developed into a more ambitious endeavour: researchers from the Faculty of Divinity and the Department of Engineering are now jointly seeking support to further their project, Casting New Values and Ethics for Sustainable Manufacturing.

The ECRs’ collaborative experience distilled into clarity many of the points that had been emerging during the earlier afternoon’s discussions about interdisciplinary and collaborative working in general. The speed-dating session was just one part of the afternoon programme organised by the STS Cambridge Network (SCaN). The event attempted to construct a vibrant platform for researchers across disciplines to connect, exchange ideas, and learn about funding opportunities for joint projects. The Research Office also offered a practical briefing on funding opportunities for interdisciplinary work, highlighting schemes that support cross-cutting initiatives.

Our first panel, What’s the value of AHSS in STEM? delved into the practicalities and challenges of working across disciplinary lines. From uncovering algorithmic bias to crafting ethical frameworks for emerging technologies, our speakers – Professor Tim Minshall, Dr Aga Iwasiewicz-Wabnig, Dr Matjaz Vidmar, and Professor Joanna Page – explored the socio-technical dilemmas and cultural complexity present in multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams. We reflected on the structures and assumptions that often constrain collaboration, and how we might reframe our individual or collective ideas about what counts as impactful or rigorous research.

The second panel, What are the nuts and bolts of award-winning interdisciplinary projects?, shifted our focus to real-world examples of successful collaboration. Dr Richard Milne, Professor Jennifer Schooling, Professor Jennifer Richards, and Dr Saheli Datta Burton shared their experiences leading projects that navigate disciplinary divides to deliver tangible social impact. Chaired by Dr Maya Indira Ganesh, this conversation offered insights into the infrastructures, relationships and mutual trust required to build effective interdisciplinary teams.

We noted that many researchers – new and old – are interested in collaborative working, but need spaces and opportunities for this to happen or made possible. Initial interactions with people from different disciplines, departments, universities or countries can be unsettling or confusing, but with time it is possible to learn how to communicate, build relationships, and make the most of our diverse skills and experiences. For this to happen, we often have to learn new ways of speaking to each other, and open ourselves to asking new kinds of questions and working in different ways. We might even have to give things up – e.g. cherished conceptual schemas or epistemic viewpoints. However, there are many benefits from stepping out of our comfort zones. We might end up working in ways that produce more equitable and inclusive outcomes, not only for the researchers involved, but also those on the receiving end of research outputs. So why can it seem as though few interdisciplinary collaborations are taking place? And how can we do more?

Interdisciplinary collaboration in context

Decades of quantitative measurement and evaluation have rewarded research that fit neatly within pre-existing academic categories. The unintended consequences include reduced scholarly diversity and increased disciplinary conformity, rewarding academic commensuration (Espeland and Sauder, 2016; Pardo-Guerra, 2022). In the UK, the Research Excellence Framework (REF) assesses institutional academic performance, shaping research agendas by establishing what counts as ‘excellent’ work, thereby privileging certain forms of academic labour. To be considered ‘REFable’, research had to align with these criteria, encouraging departments to create predetermined lists of acceptable top-ranked journals where their members are encouraged to publish.

Leading academic journals must manage the limited time of volunteer peer reviewers amid rising submission volumes; a dynamic driven by the pressure to ‘publish or perish’. The consequent culture of heightened competition reinforces specialisation and narrows ideas about what is considered publishable, often at the expense of interdisciplinary, exploratory, or publicly-engaged scholarship which are less institutionally valued or sought-after (Sørensen, 2023). As a result, ECRs are encouraged to shape their research into disciplinary pathways in order to maximise their chances in the academic job market or to get their next small grant.

Calls for more collaborative research use different (but similar) terms (multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary) to describe different degrees of integration and boundary-crossing (Klein, 2017). We might also consider what we call ‘radical’ interdisciplinarity. That is, partnerships that go beyond our disciplinary neighbours (e.g. anthropologists working with historians, or synthetic biologists working with nano engineers) to embrace truly different domains. However, academic structures and incentives often mean projects that bring (for instance) artists, sociologists, musicians, economists, engineers and geographers together take more effort to get started and to maintain, than collaborations within each of these categories.

The need for meaningful collaborative partnerships (e.g. not just between AHSS and STEM but with other non-academic project partners) is arguably more important than ever. And yet many researchers remain uncertain about how to value insights from other fields or perspectives, initiate collaborations, find suitable partners, and secure long-term support from institutionally defined funding mechanisms. For our attendees, inhabiting an interdisciplinary ‘room’ meant finding new skills and different ways of working. This might involve finding a ‘safe harbour’ in which to feel comfortable, and seeking out resources to help navigate interactions with others in that space (Calvert, 2023).

To conclude: our recipe for AHSS-STEM collaboration

Our discussions revealed that different disciplines have distinct ways of generating ideas and problematising research questions. STEM projects are often framed as exercises in problem-solving, while AHSS stresses the importance of exploring research questions and their implications from different perspectives. This difference is not a gap to be bridged, but a dynamic tension that can ignite creativity and produce more helpful outcomes if they are brought together. Some challenges demand a fix; others for understanding, storytelling, or a reframing of the problem itself. Many benefit when multiple approaches are combined.

Disciplinary boundaries shape how we think, what we value and how we measure success. Indeed, the framing of our event as ‘AHSS meets STEM’, may have redrawn unhelpful boundaries between researchers who do not self-define according to these labels. Meaningful collaboration often asks us to look beyond these disciplinary boxes and requires openness and humility to accept other ways of doing things, and to de-construct our prior knowledge.

We learned that while institutions, departments, and teams offer structure, it is people who make partnerships thrive. The most rewarding collaborations emerge not from strategic planning alone, but from long-term relationships built on trust and mutual curiosity. Our favoured recipe for AHSS-STEM collaboration therefore combines a good dose of humility, a willingness to sit with uncertainty, and a commitment to equity. Together, these elements level the interdisciplinary playing field so that everyone is challenged, and everyone is heard.

We thank the West Hub Small Grants Scheme for supporting the event that informed this piece, and the two reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive feedback.

Reference list

Calvert, J. (2023) A Place for Science and Technology Studies: Observation, Intervention, and Collaboration. Cambridge: The MIT Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14594.001.0001.

Espeland, W.N. and Sauder, M. (2016) Engines of anxiety: Academic rankings, reputation, and accountability. 1st edn. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Klein, J.T. (2017) Typologies of Interdisciplinarity. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, pp.21- 34. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198733522.013.3.

Pardo-Guerra, J.P. (2022) The Quantified Scholar: How Research Evaluations Transformed the British Social Sciences. 1st edn. New York: Columbia University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7312/pard19780.

Sørensen, K.H. (2023) Affordances, affects, and animosities: Exploring research cultures. EASST Review Volume 42(1), 22–26. Available at: https://easst.net/easst-review/easst-review-volume-421-july-2023/affordances-affects-and-animosities-exploring-research-cultures/

Author biographies

Dr Valeria Ramirez is a Research Associate at the Policy Evidence Unit for University Commercialisation and Innovation in the Department of Engineering at the University of Cambridge. Her research explores socio-technical quantification processes and measurement conventions, and currently focuses on knowledge exchange (KE) metrics in UK higher education. Her doctoral work examined how communication professionals navigate digital measurement practices. Originally trained as a journalist, Valeria has over 15 years of international consulting experience in Mexico, Spain, and France, where she supported organisations in sectors including finance, law, and pharmaceuticals with strategy and crisis management.

Dr Louise Elstow is a research associate at the Centre for Sustainable Development in the Department of Engineering at the University of Cambridge and a consultant in resilience and emergency management. She specialises in knowledge creation and workforce diversity in in various fields, including climate change adaptation and ‘resilience’ (in its various guises), contamination and CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear) events, disaster management, and societal resilience.

About the STS Cambridge Network (SCaN): SCaN emerged from a shared desire to connect and support interdisciplinary scholars working at the intersection of science, technology, and society across Cambridge. It was created to address the limited opportunities within the University for STS and STS-adjacent researchers to connect – both with each other and with broader regional and international STS communities. Since its informal beginnings at the 2024 4S-EASST Conference in Amsterdam, SCaN has grown into a vibrant, cross-institutional community, engaging in events from seminars and film nights to museum visits and collaborative workshops.